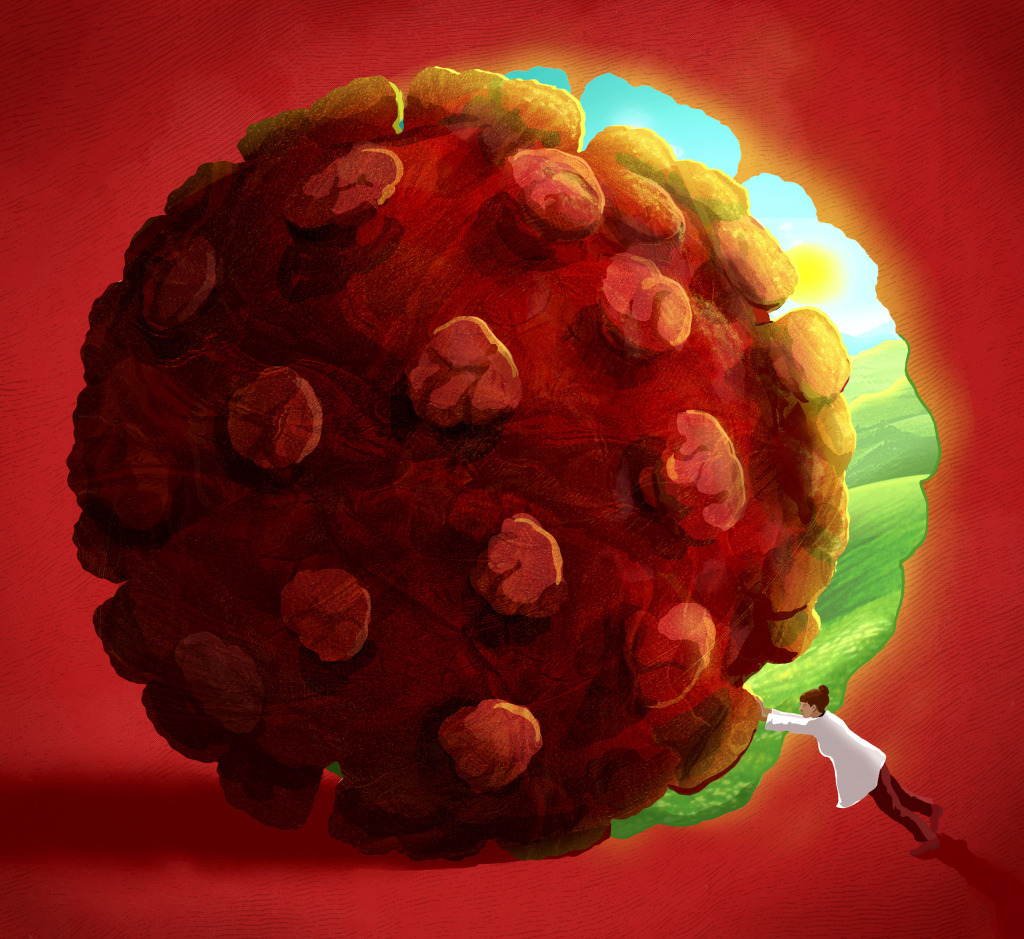

Inspired by the wonders of the scientific world, Sam Falconer’s art ignites a sense of awe and curiosity, drawing viewers into a kaleidoscope of riotous colours and intricate details. Through his work he brings science to life, making it accessible and enchanting for all.

Sam Falconer

A Science Fantasia

How did you arrive at your fantastically vibrant and complex style of illustration?

Thank you first of all for the nice description. My style has developed very gradually over the years through a mixture of experimentation, happy accidents and an itch to improve on previous pieces that I wasn’t quite happy with. There has also been an influence from art director’s requests or suggestions, which have often taken me in a different direction and been very helpful in exposing me to new possibilities.

When starting out my work was much more muted, but over the years the colour has become quite a central theme and an increase in complexity. In freelance illustration oftentimes you are working to fairly short deadlines which has forced efficiency into my process which has then in turn allowed me to increase the vibrancy and detail of the work to something I am happier with.

What made you decide on science as your area of specialty?

I developed a deep interest in popular science books and media at university and it just became the most interesting subject that I could imagine working on. My final project was a children’s book exploring a fantastical world of atoms and seeing people’s responses to that was very rewarding and helped to cement this direction.

I have and still do work on projects that aren’t directly science-themed, but many of my most enduring and fulfilling projects have been in this area. It’s a consistent theme of interest in my personal work.

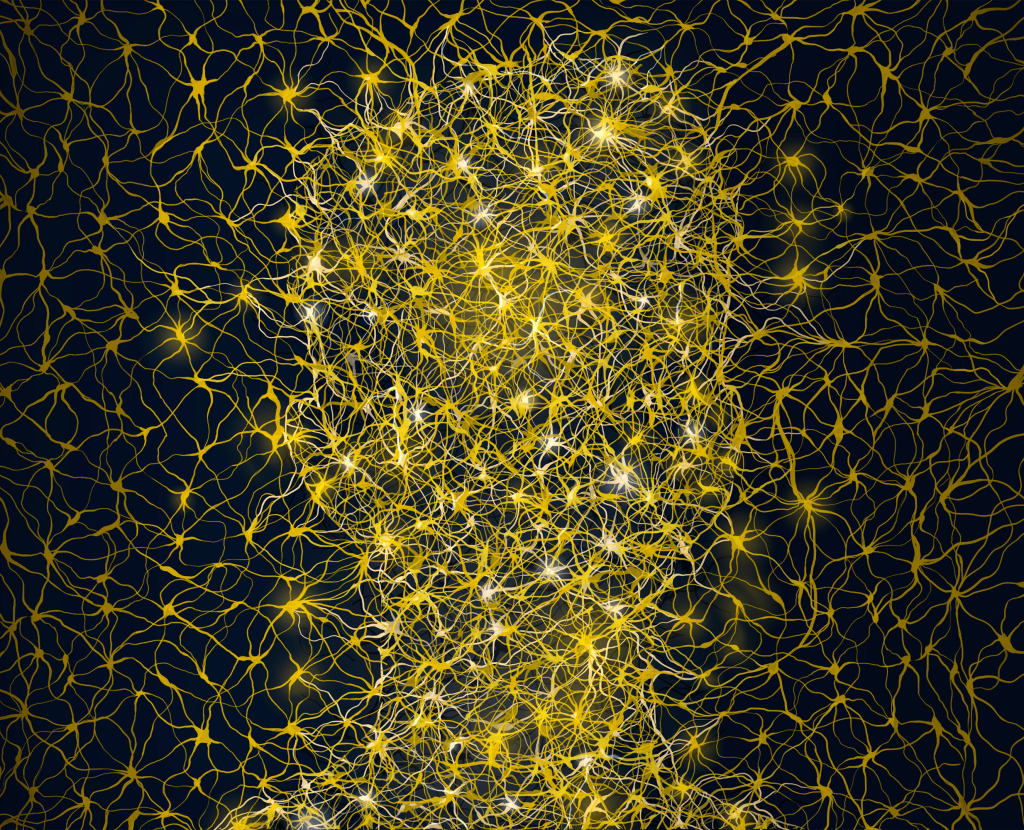

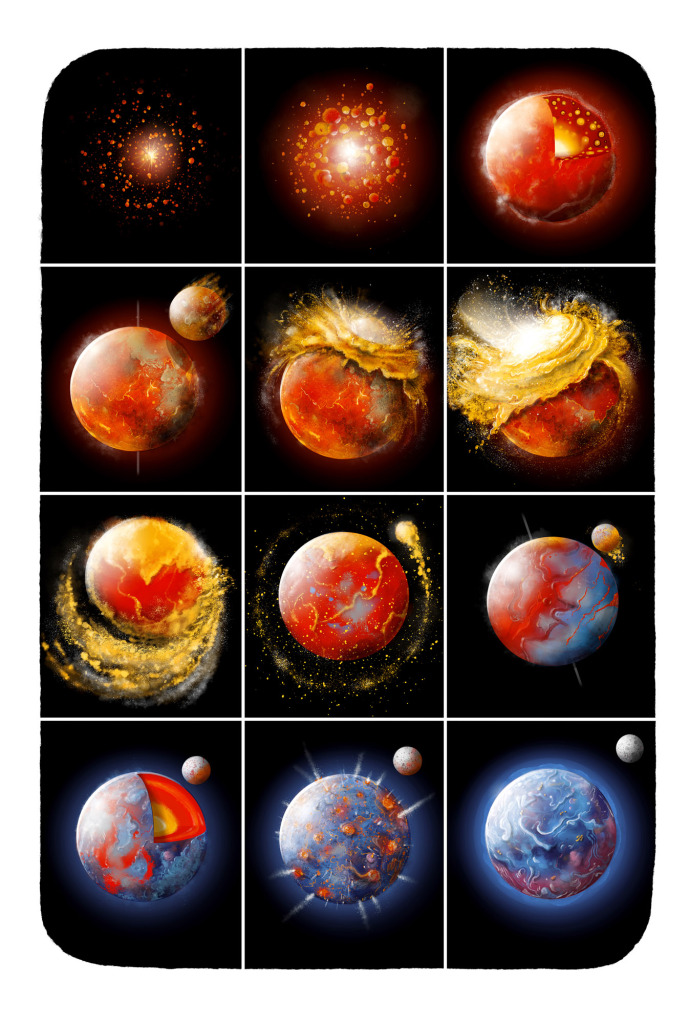

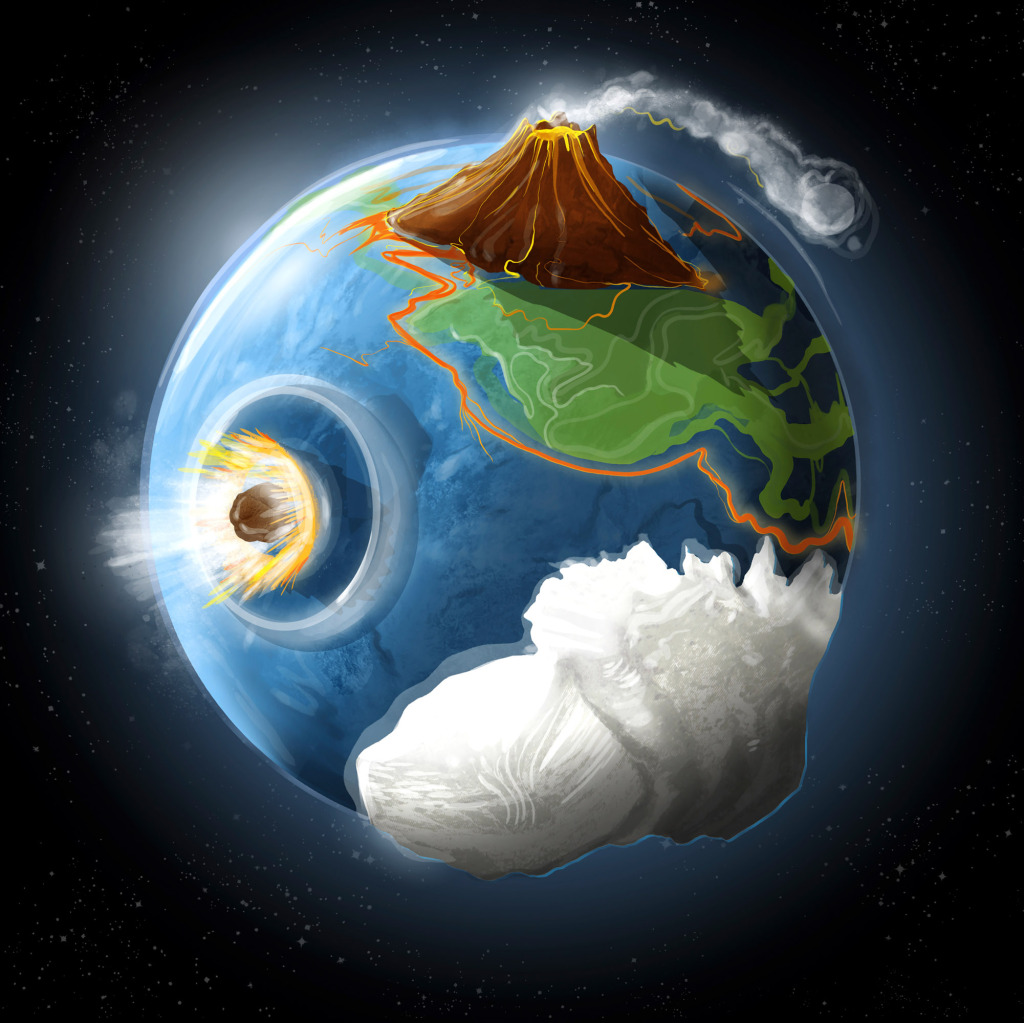

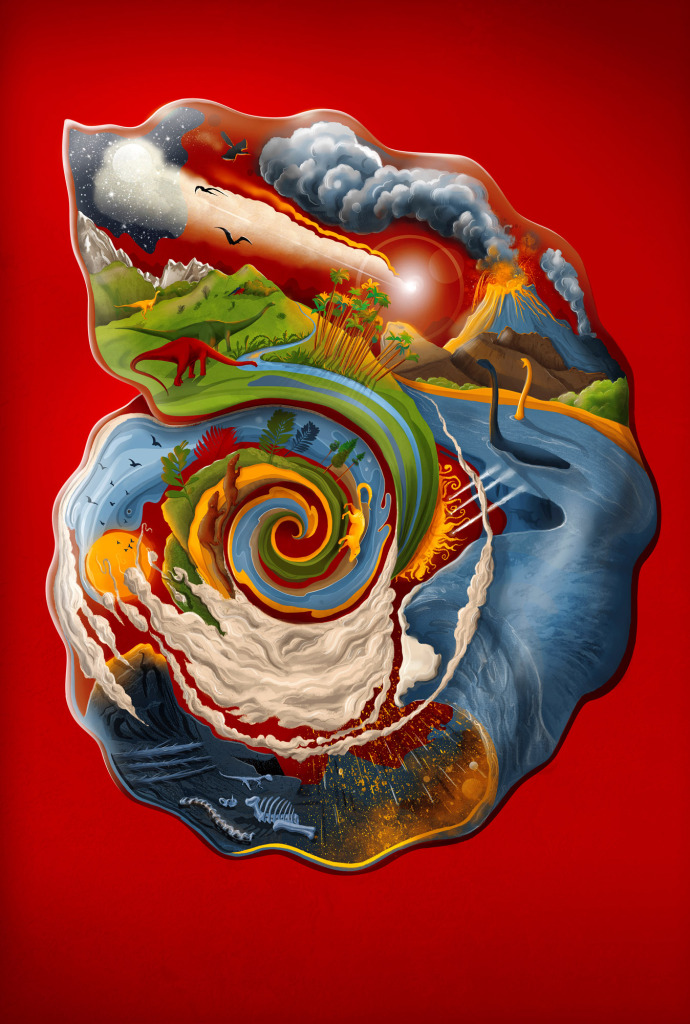

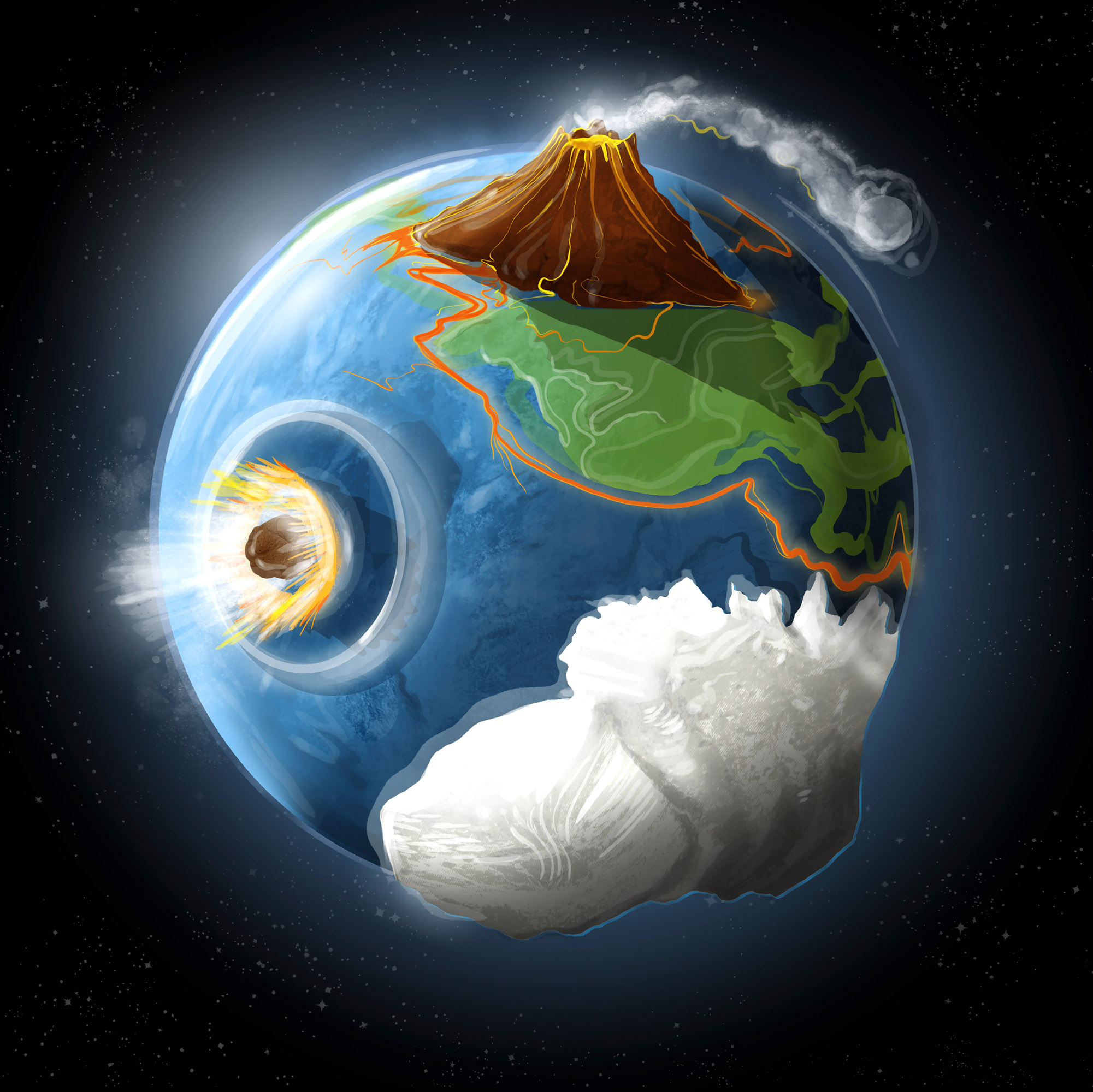

A key event was a solo exhibition at The Coningsby Gallery in 2018 where I developed a series inspired by landmark moments in the history of the universe and tried to present them in a way that communicated their relative positions in deep time. Working out how I could translate these topics into an engaging visual style whilst also communicating some complex ideas was a real challenge, but led to some important personal breakthroughs in how I see my work and what might be possible.

What kind of research do you undertake before starting a project?

This varies a lot depending on the project. Sometimes a commissioner will already have a rough visual in mind or a narrow topic of focus, so the task there is more in the purely visual decisions. On the other hand, if it’s a more involved piece such as a scientist’s portrait then I will trawl the web and try to understand their defining contributions with an eye always on how I could translate that visually.

For other pieces such as the one I am currently working on of a Neanderthal, I watch videos, read researcher’s press releases or articles in popular science magazines and then form a source document of key topics that I can refer to whilst creating the artwork.

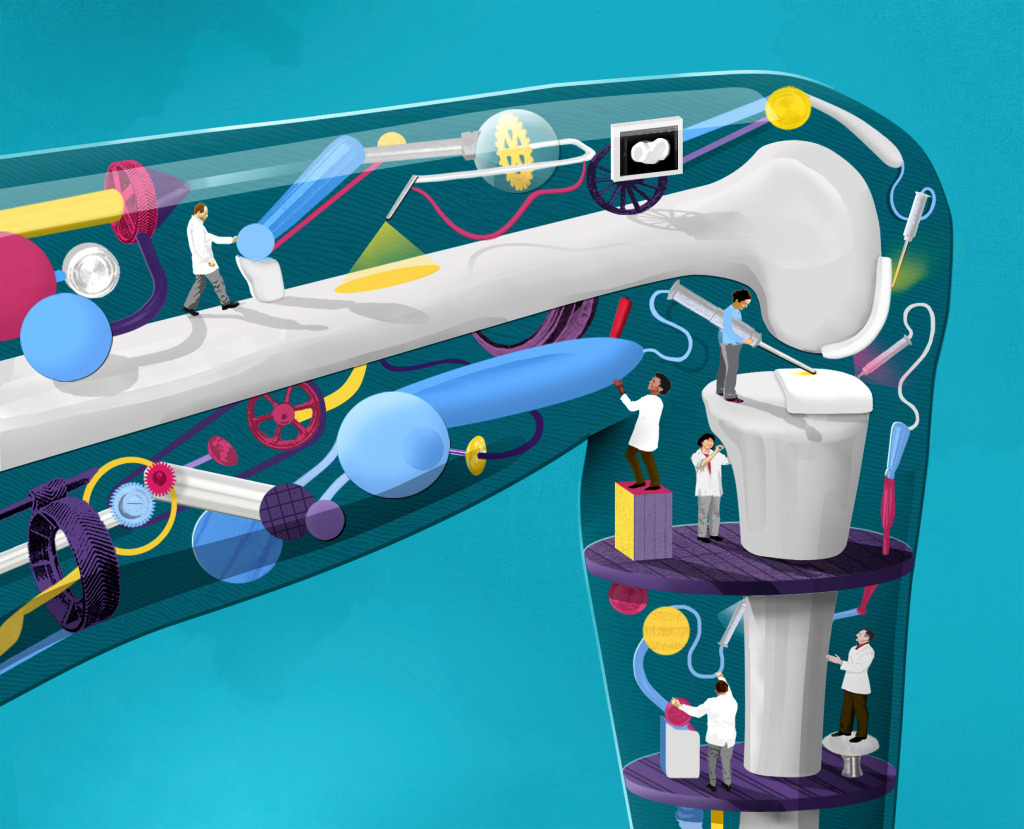

I have also recently worked more directly with scientists who are looking to present their research with an engaging illustration. This has been more of a listening exercise in trying to understand the technical details of what it is they are studying and how I can translate that into a successful image.

How do you balance capturing scientific concepts accurately while maintaining an artistic flair?

This has been a very interesting challenge. I take pride in the details and would like to think that if someone with subject expertise decided to take a closer look at one of the more complex science-inspired illustrations then they would find elements that are relevant and fairly accurate. Having said that my primary job is to bring a subject to life with an interesting and engaging visual. I’m usually working in the language of contemporary illustration to communicate a certain perspective.

With editorial jobs strict accuracy isn’t often too much of a concern for the art director as the content is usually for the general reader.

In my personal work, I perhaps lean more towards accuracy as an aim but it really depends on the idea. I think I often find the balance by rendering the individual objects and details fairly realistically, but then I’m sometimes much more experimental in the framing, shape or broader composition.

Every project is different and this is something I’m always figuring out as I go along.

What do you find most challenging about translating scientific ideas into visual representations?

I think it’s probably retaining the maximum amount of accuracy whilst producing something that I find visually engaging. There can also be a difficulty in illustrating topics related to phenomena outside of our normal day-to-day experience. Often they aren’t easily translatable into clear visual representations or accessible concepts.

Colour is a powerful characteristic of your work. How do you decide on the palette and style of an illustration?

Over the years there are a few approaches that I have found work quite well through trial and error and I try to keep the key colours down to three or four and then shades within those.

I am often developing the palette in steps as I progress through an image and I try and introduce a bit of randomness here and there to keep things interesting.

It can be easy to rely on a previously successful formula over and over again and that is something I try to be mindful of.

Your creative technique is as complex as the ideas you illustrate. Could you explain the different techniques involved in the production process?

The ideas phase is a combination of scribbles and thumbnail sketches in a notebook and just sitting and ruminating on an idea. Once the idea is settled I will start to lay out the key shapes directly into Adobe Photoshop with a combination of colour fills, the pen tool, the lasso tool and my tablet and digital brushes.

From here on there are a few different approaches. Sometimes I will go ahead and paint in the rest of the image with these same tools. On other pieces, I will start to collage using public domain imagery and then alter these elements before applying colour and pattern. There are then also textures that I often include.

Recently it’s usually a combination of all of these things and it’s something that’s always evolving.

Which artists or movements have had the greatest influence on your work?

It’s hard to say. I love detailed, sophisticated and technically proficient art and illustration wherever I see it. With the nature of modern media, influence is diffused among thousands of pieces, many of which I suspect I am not even conscious of. I think the work has evolved from hundreds of small influences over the years, experiments with different tools, being inspired by certain aspects of other illustrators’ work, feedback from peers and teachers, art directors, happy accidents, a love of drawing and seeking out visual novelty.

There’s a bit of a contradiction in illustration in that you are often obsessing and fully absorbed in creating your very own world, making a style that is unique to you as far as possible but still hoping that this work appeals to the tastes of commissioners and a wider audience.

It’s a push and pull between this obsessive tinkering and real-world feedback.

What role do you think illustrations play in communicating complex scientific concepts to a broader audience?

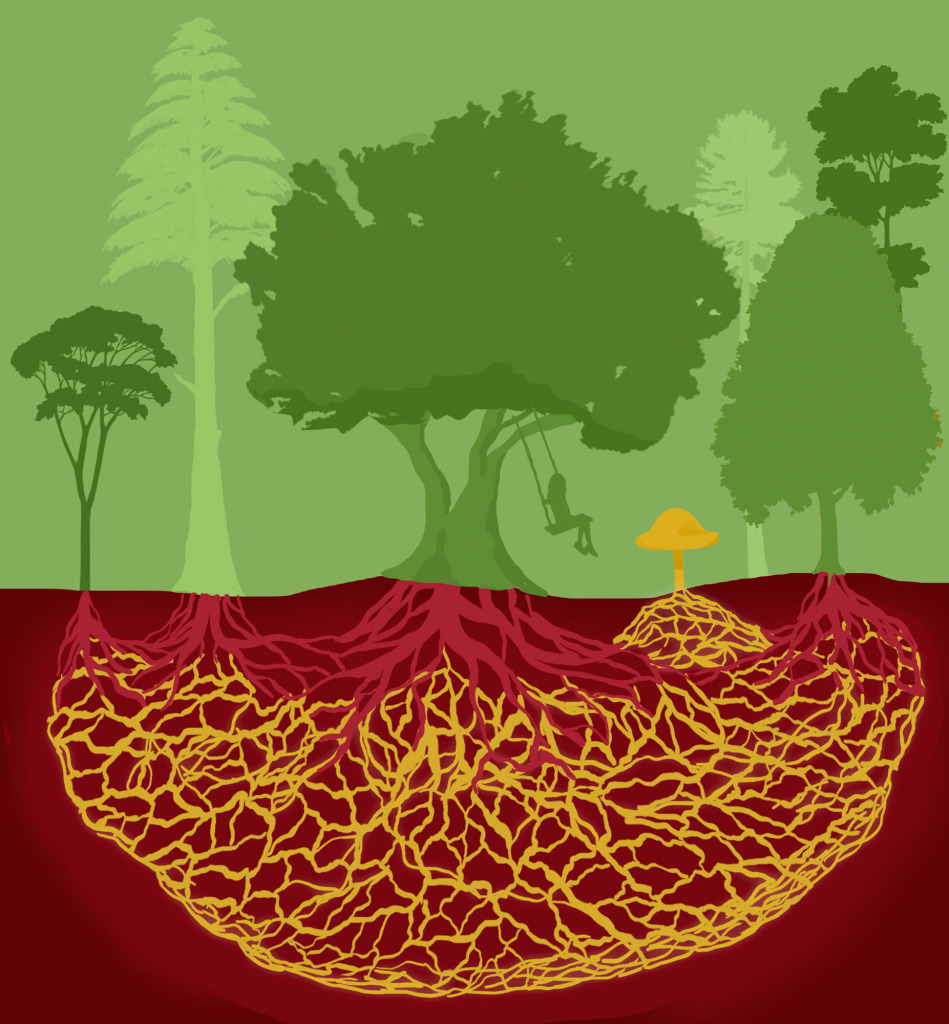

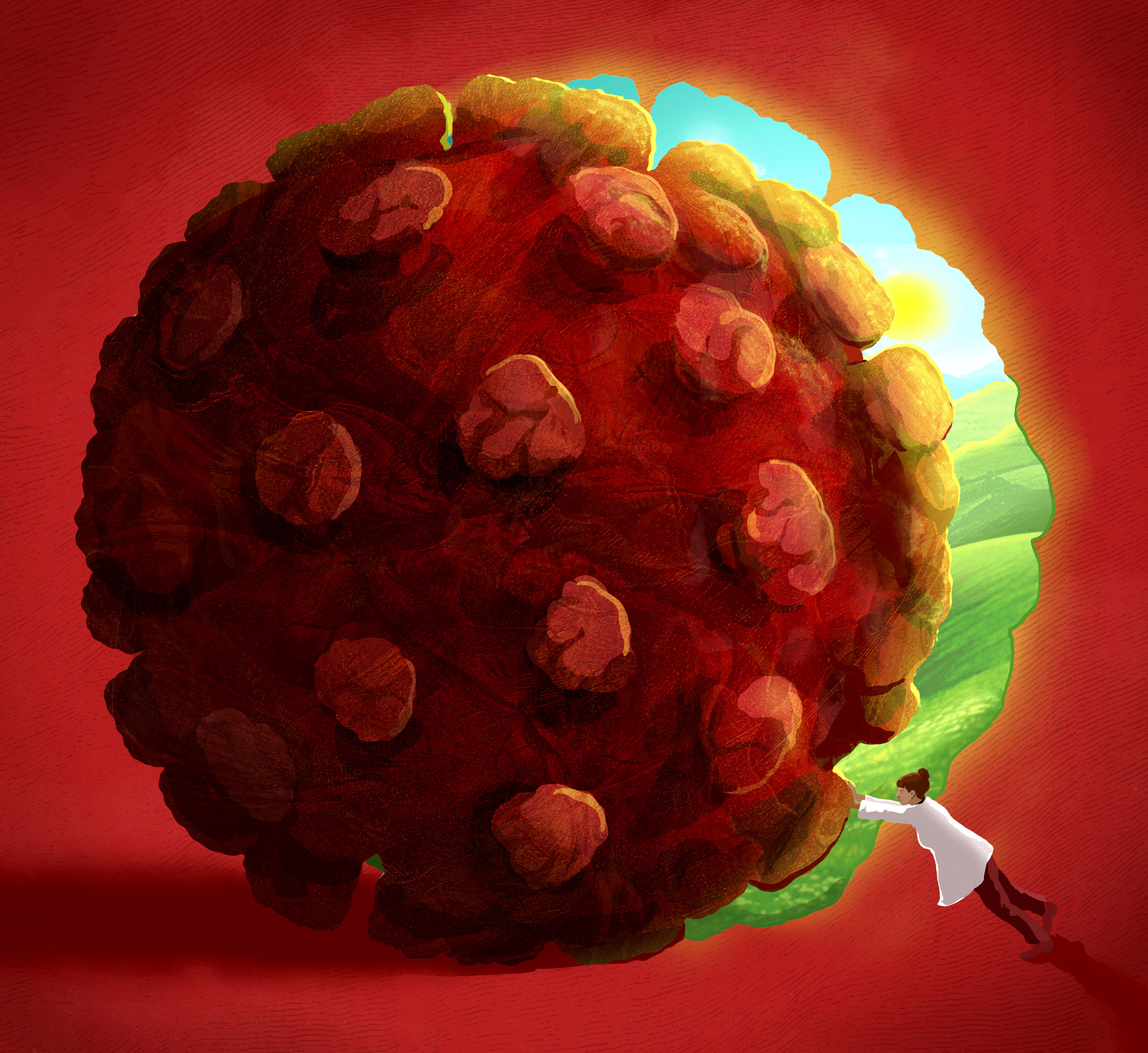

I think illustrations can often play a uniquely effective role in communicating these ideas. There are certain tools at the illustrator’s disposal that can have an advantage over straight photography for conceptual communication.

I think a good illustration can also help to make a topic more accessible to a general audience. Many complex topics in popular science can be translated into an engaging visual metaphor that can draw the reader in to go deeper.

There are so many beautiful styles to choose from too that can be cleverly matched with the right topic.

What is your favourite commissioned piece and why?

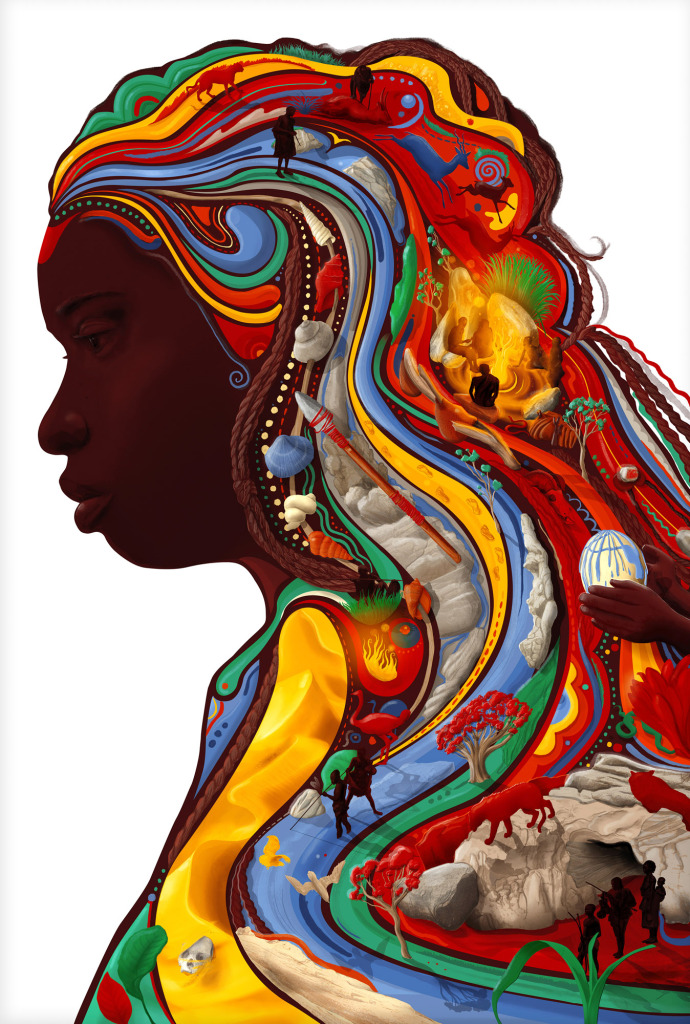

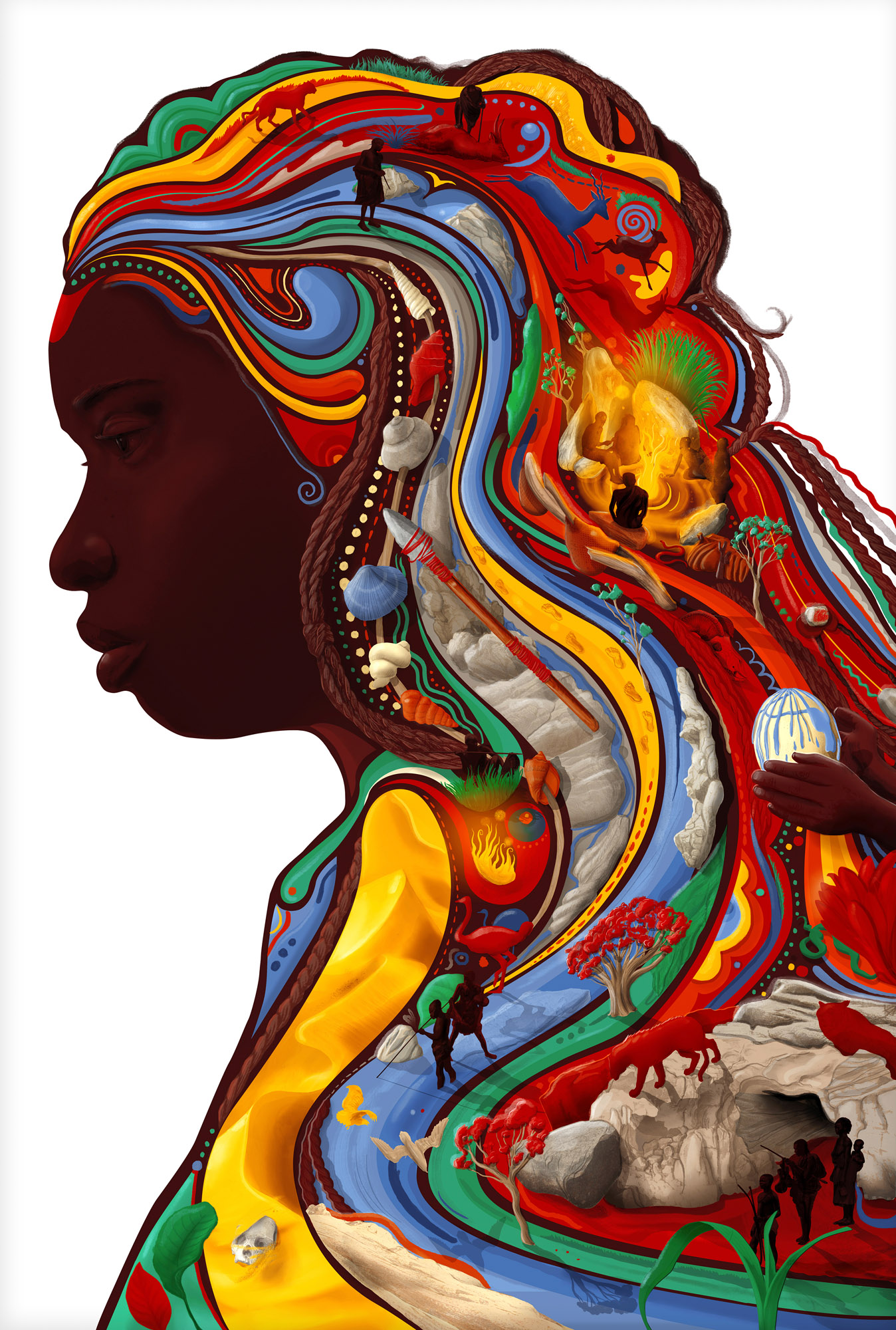

Mitochondrial Eve is one of my favourites. It was a prominent piece in my Deep Time exhibition put together with Debut Art and the Coningsby Gallery. It was a landmark illustration for me in that it was the first time I had managed to combine a complex scientific topic that I had chosen with this flowing and detailed visual style.

The exhibition was inspired by key moments in the history of life, the universe and human development; a cosmic timeline, giving a sense of where and when we find ourselves in the early 21st century. It was also the first time I shared these pieces with people in a gallery setting.

Is there anything else you would like to share with our audience about your work or your passion for art and science?

Just to say thank you to everyone who has appreciated, purchased, commissioned me or engaged with the work over the years.

Illustration can be a solitary pursuit punctuated by special moments of connection.

Thank you for the insightful and thoughtful questions and to the team at Science Photo Library for your support.