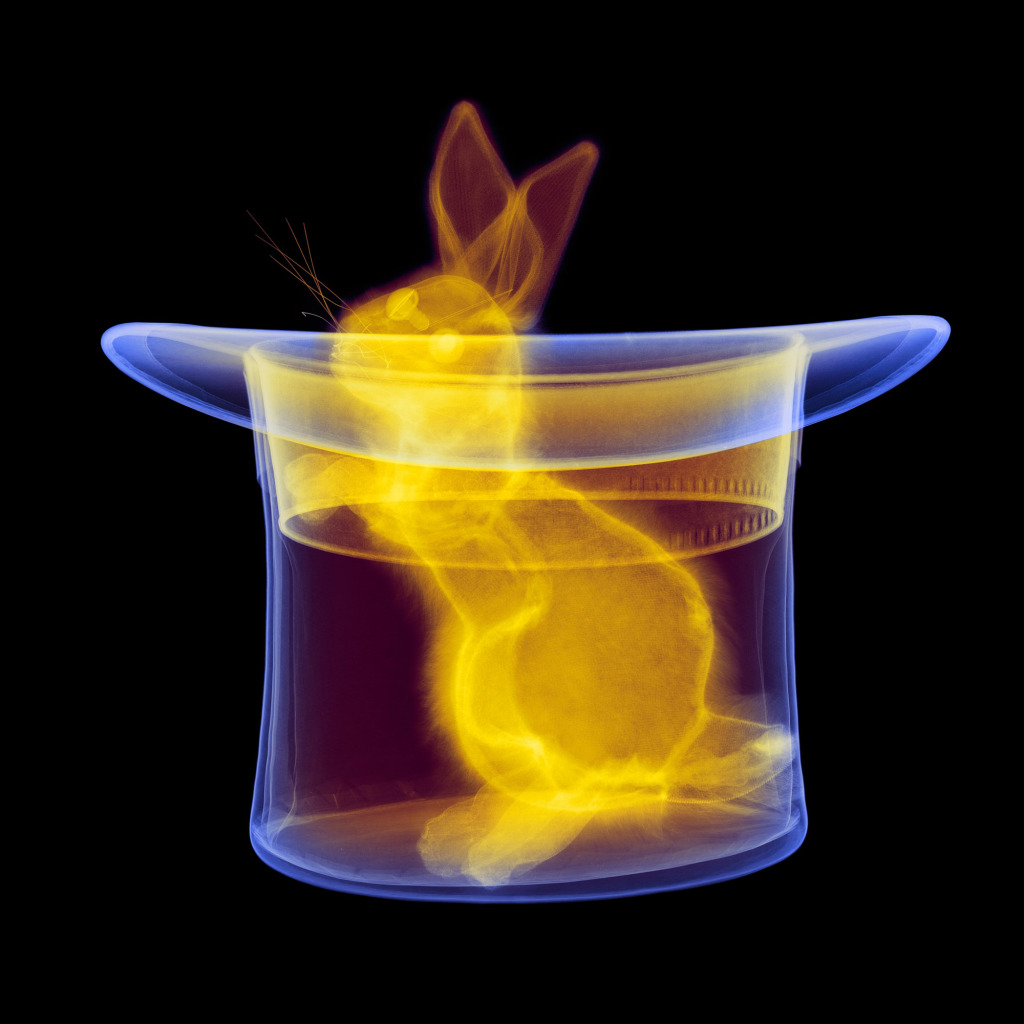

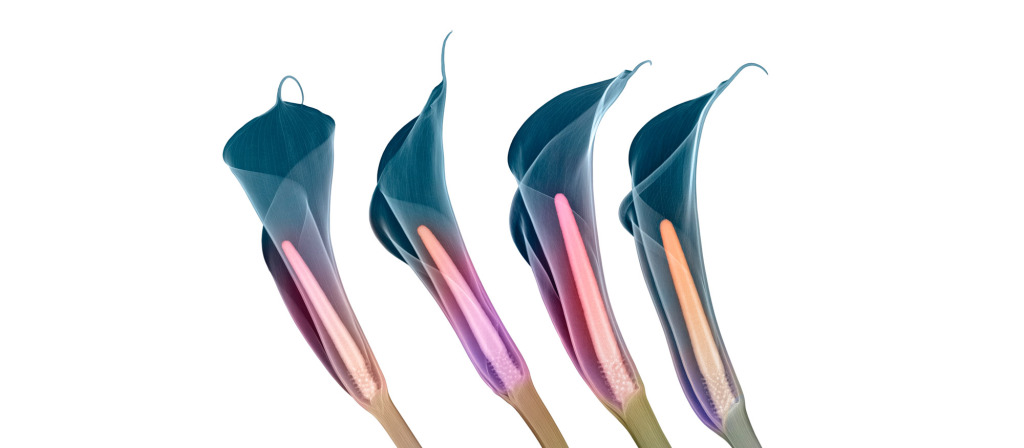

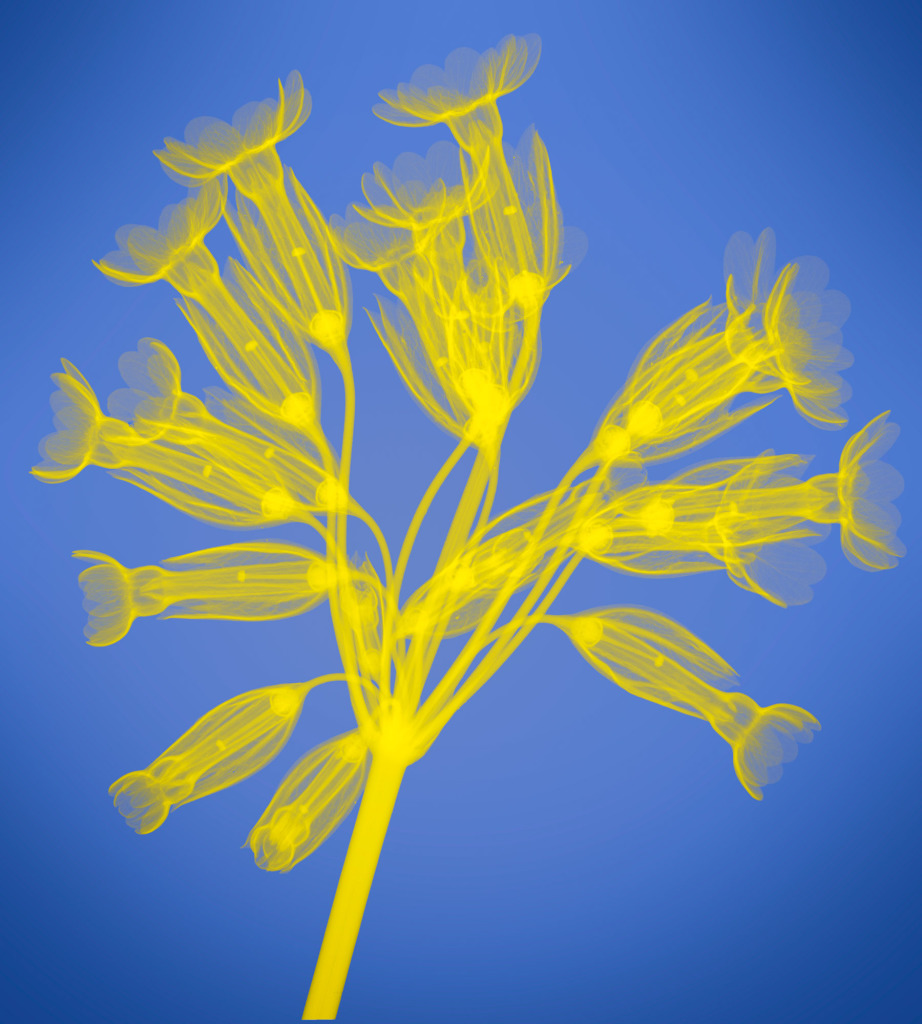

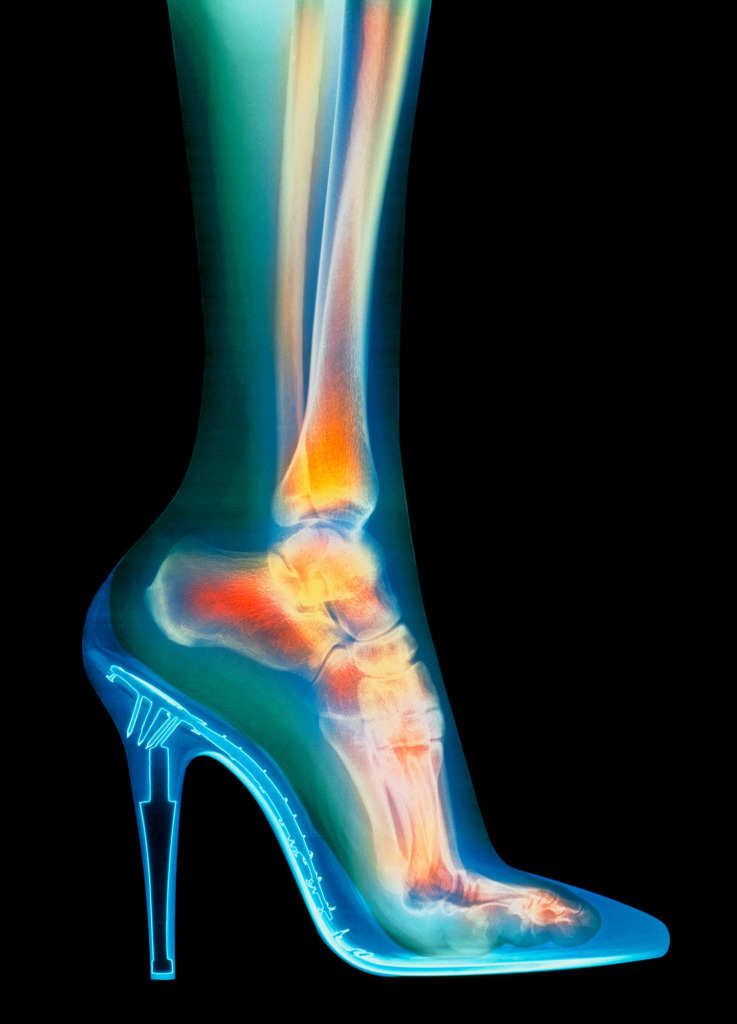

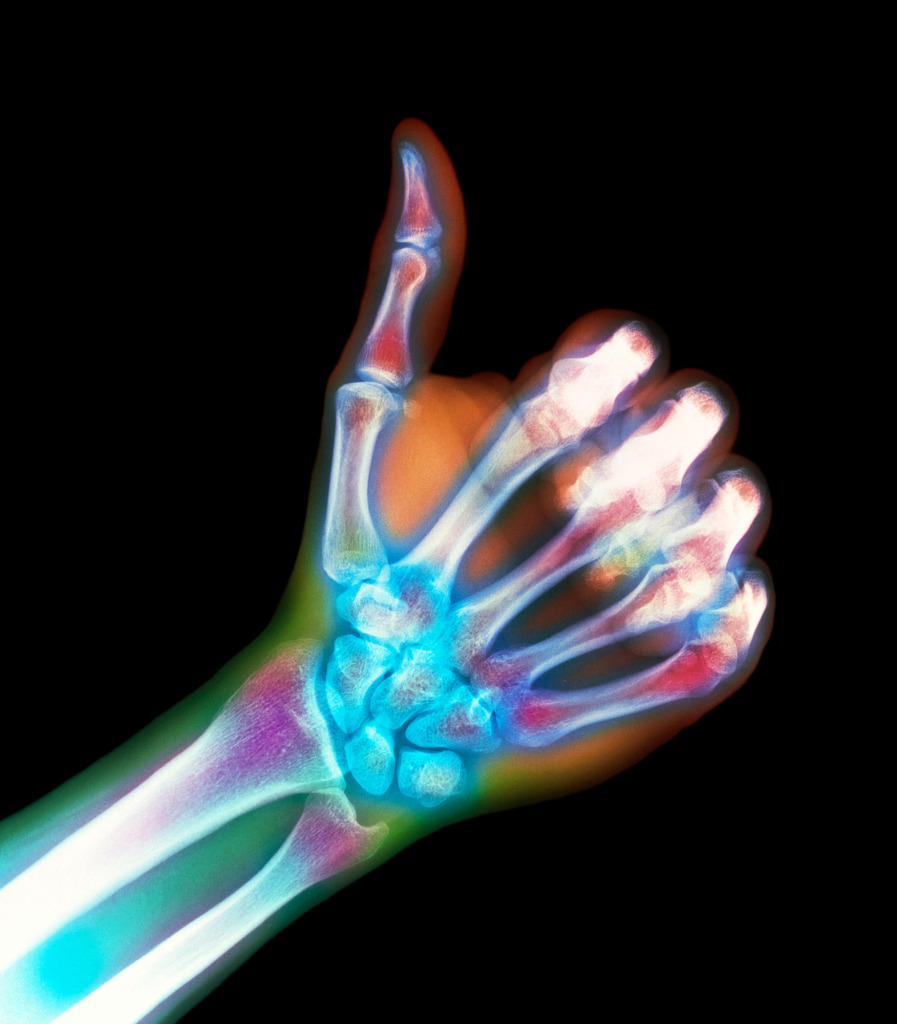

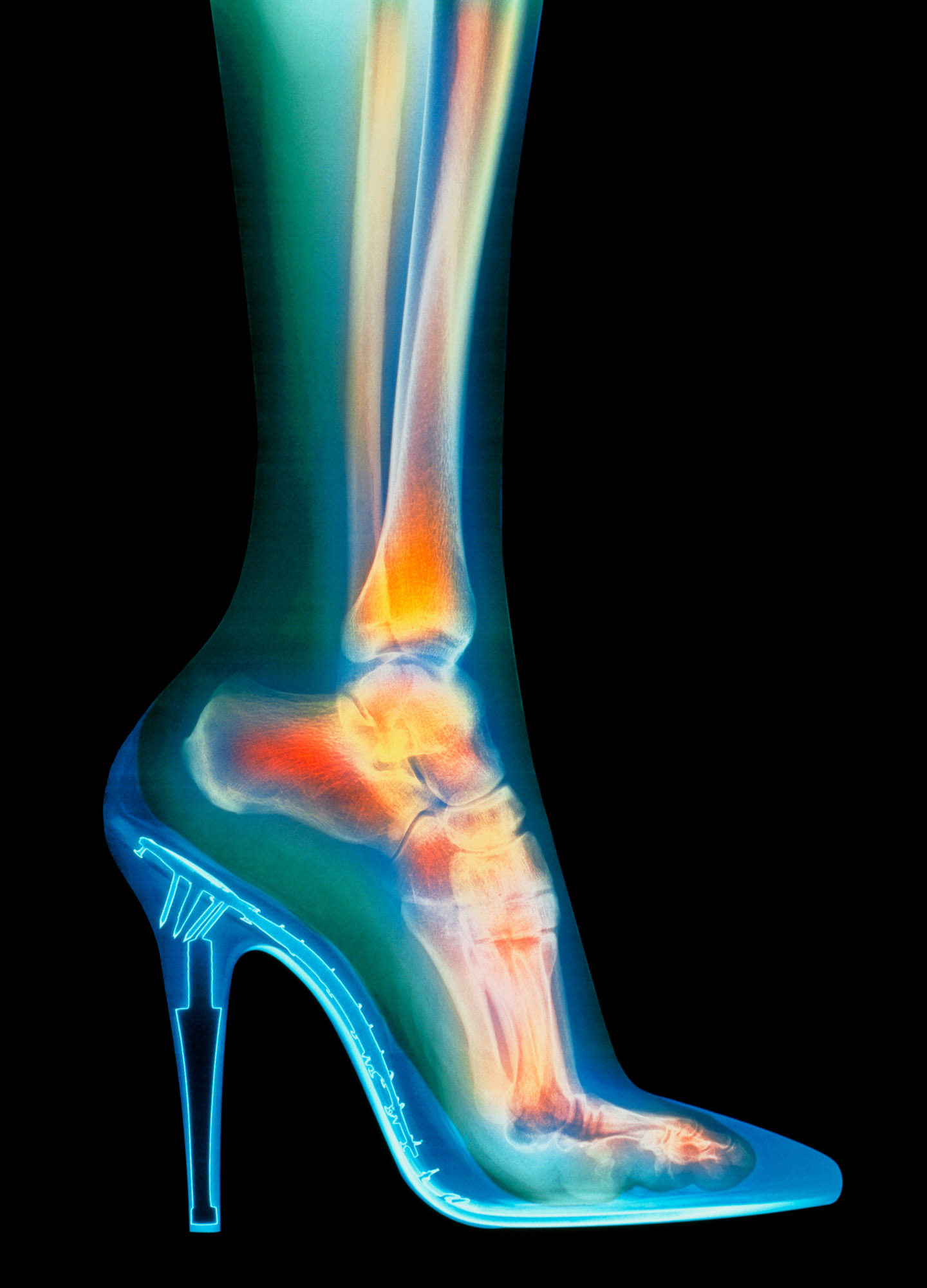

Hugh Turvey is an X-ray artist. We took the opportunity to ask him a few questions about his move from traditional photography to X-ray imaging, which expanded his technical knowledge and creativity.

Hugh Turvey

Capturing a shadow

When did you first become aware that you wanted to be a photographer and work in the creative industries?

My aunt was an artist in the Bahamas and I always wanted to be like her.

A large canvas of her work has hung in our family kitchen in the West Country for as long as I can remember. Her work is illustrative, graphic with figures, landscapes, and objects overlapping, interweaving and blending into each other; a flower, butterfly, a musical score, a page of calligraphy combined in an intriguing composition to produce a multiple reality.

Although a very different medium, X-ray imagery does share similar characteristics. It looks under the surface of objects, through different layers of density, casting shadows of what it finds in strange and unusual perspectives. Perhaps all those meals eaten under the gaze of her painting did unconsciously influence the direction of my work.

It was my aunt who gave me a Konica 35mm film SLR camera with one detachable lens when I was around 10 years old. It was an older generation camera which I quickly traded for a Pentax ME Super Black with a very bright 50mm F1.2 lens. I love the technicality of photographic capture and the frozen moments in time as expressed by Henri Cartier-Bresson’s ‘Decisive Moment’. I have certainly been inspired by photographers such as Ansel Adams, Elliot Erwitt and Harold Edgerton.

How did your career evolve from traditional photography to the specialist field of radiography?

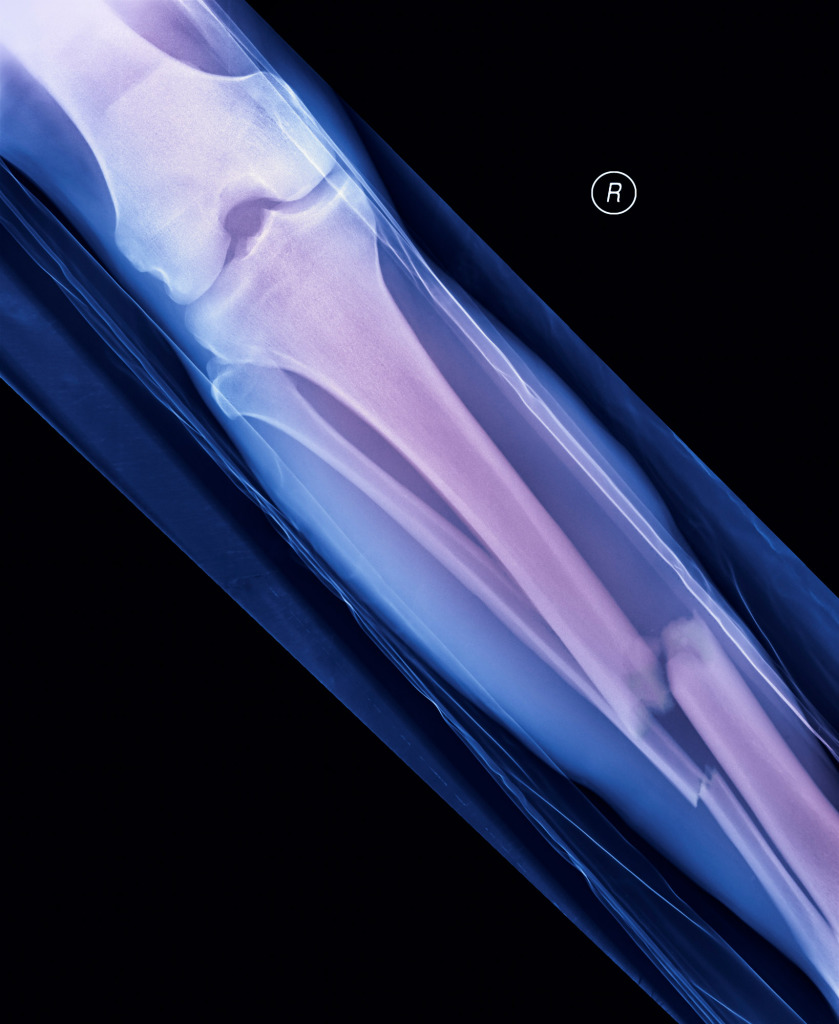

I trained as a designer/art director and then as a photographer, starting a 4-year apprenticeship with music industry photographer Gered Mankowitz in 1994. This included photographing bands such as Oasis, Phil Collins and printing the Hendrix and Rolling Stones archives. Through some music industry friends, I was asked to do a personal commission which required a bone image. Using an X-ray seemed a perfect solution.

The Royal Free Hospital was just up the road from Gered’s Studio and during a lunch break, I went to seek advice from the Head of Radiology, who evidently had an interest in photography.

The parallels between photography and radiology were striking. Radiographers were using huge 17×14 inch film which was considerably larger than the medium format film used in the Hasselblad at the studio. It intrigued me and provided a whole new area of technical expertise to explore.

But the ability to see into objects was what really caught my attention. I had only ever captured images with the light rebounding off the surface and suddenly here was a ‘light’ that could see into things! For me, this was a new X-ray photographic aesthetic, one that had little visibility in the creative world at the time.

How did you gain access to an X-ray machine and who taught you how to use it?

After a solo exhibition of creative X-rays in 2009 at the Oxo Gallery in London, I became the British Institute of Radiology Artist in Residence. The BIR is the international organisation for everyone working in X-ray imaging, including radiation oncology, medical physicists and the underlying sciences.

This position was a gift to my growing interest in becoming an X-ray artist. It introduced me to radiographers working in different fields, using a range of techniques. I was able to learn rapidly from some of the best practitioners in the profession with access to state of the art equipment.

I was always interested in the technical side of photography so it wasn’t that difficult to transfer my allegiance to X-rays.

How challenging is the process of creating X-ray images?

Radiography is also known as ‘shadow photography’. When you create an X-ray image, you are capturing a shadow of the densities within the subject. The size of an object X-rayed can present serious challenges as the machine only captures at a 1:1 scale and the film is only 17×14 inches; so, for example, the motorcycle X-ray was made up of approximately 50 pieces of film taken one after another at varying exposures.

These were then digitised and painstakingly stitched together on a computer, making sure the pieces matched and fitted together accurately. This method allows for capturing amazing detail but is costly in terms of time, film, digitization, and patience. It took around two months to complete. It was the first time a large object had been X-rayed this way and we were learning on the job.

Working with radiation has its own constraints. All imagery is created in huge concrete/lead bunkers. I’m only inside the bunker for composition and setup after which I exit and slide the lead door shut. The exposure variables (kilovoltage, milliampere and time) are managed by a control unit outside the bunker. Film processing takes about eight minutes per sheet to complete.

You’ve incorporated other diagnostic imagining techniques such as MRI into your repertoire. Is this merging of technologies something that particularly interests you?

I have been working with analogue film X-rays for over 25 years and enjoy interweaving and it seemed natural to incorporate the many newer digital techniques including MRI, CT and micro-CT (volumetric reconstruction).

These techniques all provide different visual opportunities that can assist with detail capture and create something new.

Why do you think the public is fascinated by X-ray imagery?

The ability to see the unseen.

The comic fantasy of X-ray specs made real and ultimately the deeper visual appreciation of the world around us.

With technology changing so rapidly how do you see your work developing in the future?

All visual arts are defined by the scientific invention of ‘artistic medium’. Admittedly, when the scientists were inventing non-invasive MRI and CT for example, I am sure artistic application was not in the specification. However, the ability to see the world in new ways will always intrigue me and I look forward to the new creative potential of emerging imaging technologies.