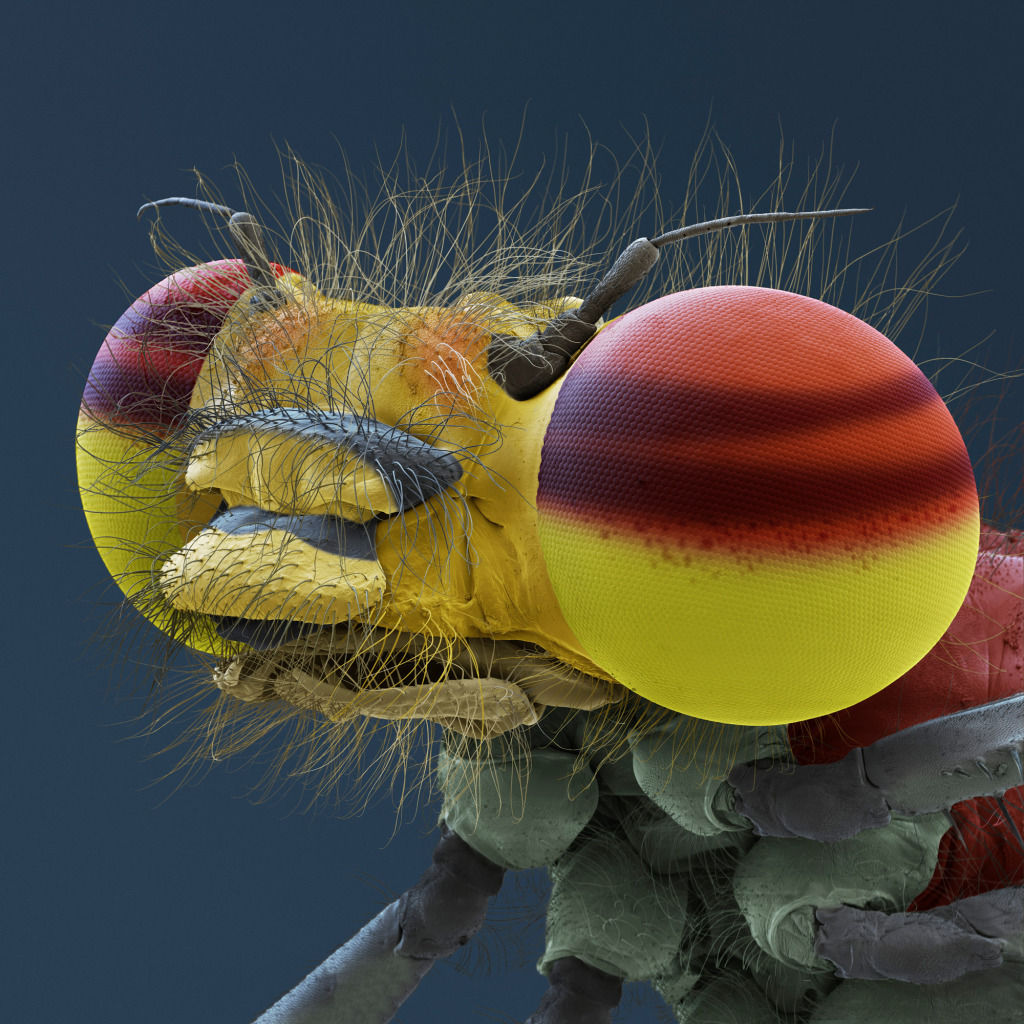

Oliver Meckes & Nicole Ottawa take you on a fascinating journey into worlds within worlds. Discover the beauty and intricacies of their wonderful microworlds.

Eye of Science

Fascinating beauty of worlds within worlds

How did you first become interested in science and microscopy?

OLIVER: For me it was a ‘toy’ microscope I got at the age of 12, I started photographing at the age of 14 and combined both later.

NICOLE: I was dissatisfied with the illustrations I saw in scientific books during my studies and wanted to do better, so asked for an internship at Kage’s.

Could you give us some background on your experience and training under Manfred Kage at the Institute for Scientific Photography?

OLIVER & NICOLE: We began at the Institute in the pre-digital era. We were taught analogue scientific photography including developing film, making prints and transparencies. Manfred was best known for light microscopy and extreme macrophotography, including large format 4”x 5” cameras, so there was a lot of equipment and experience at the Institute. We also had contact with endoscopy, X-ray, schlieren and Kirlian photography.

We both attended a course for basic instruction in scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at the University of Munster. After that we were allowed to work on the Institute’s SEM. These were the early days, before Photoshop, when colour was added to the black and white SEM image using filters of orange, blue or green. Oliver started colouring with dyes and later composing works in multi-colour in the darkroom- all with chemistry and film.

How did Eye of Science begin?

OLIVER & NICOLE: In the mid-nineties SEMs were confined mostly to research institutions, corporations and universities. They were hideously expensive. For these reasons it was rare for an individual to own one in a freelance capacity. After half a year of research we found an eleven year old SEM used in the semiconductor industry that was being replaced. It was running fine and we were able to buy it for 10% of the price of a new one.

Computer technology had just reached the level to handle digital imaging, producing 4 megapixel images. The cost of the computer, monitor, scanner and printer was as high as the cost for the microscope! Our first Mac had floppy discs, 500MB hard disk (!) and 16MB RAM.

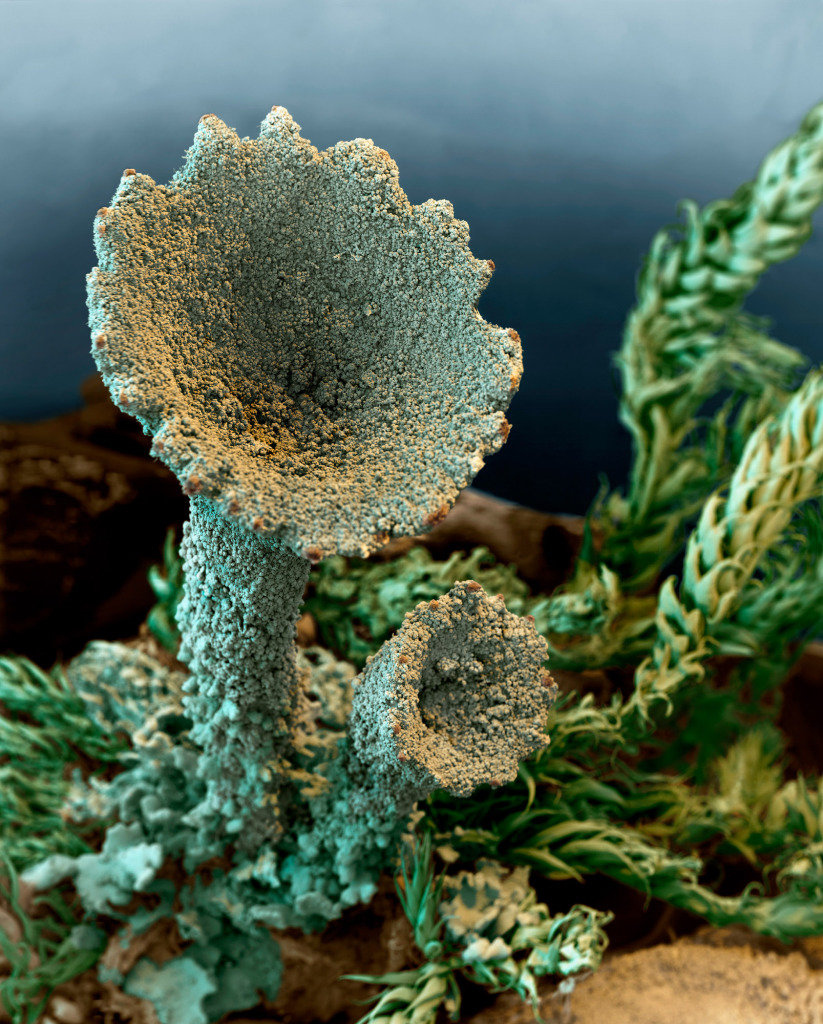

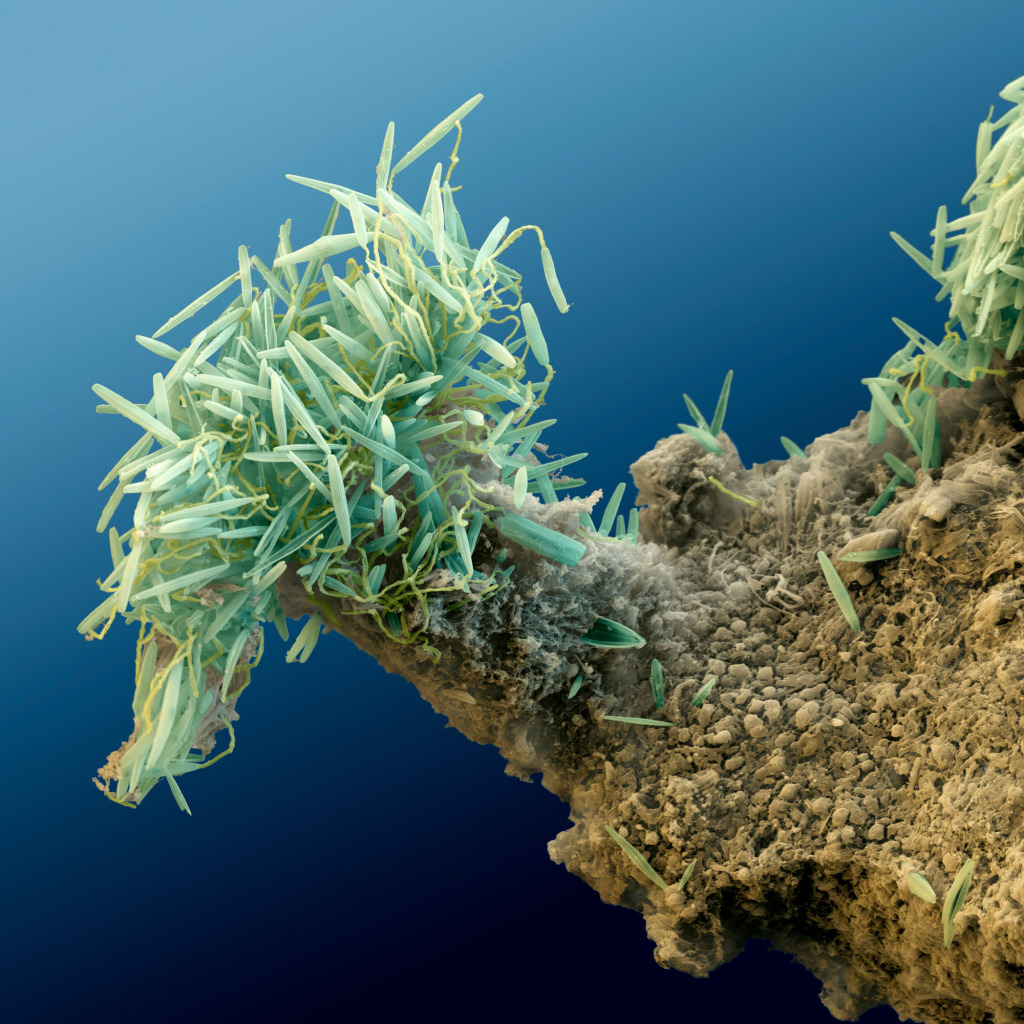

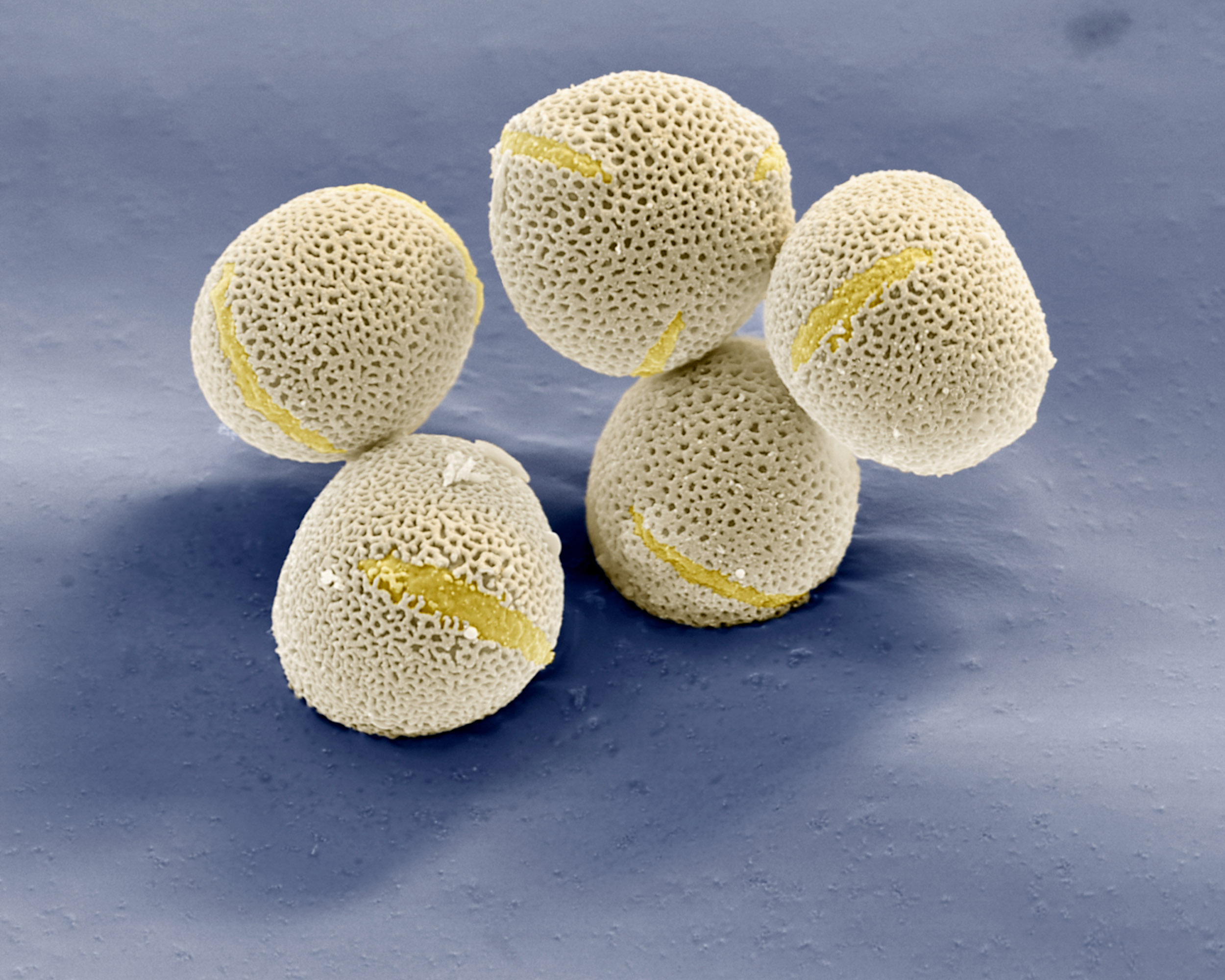

There was a startup company in Halle who converted our analogue SEM to digital in 1995 – with great images in return. First things we photographed were pollen, bacteria and herbs – all things we had easy access to. With these images we trained ourselves in digital imaging (Photoshop 3.0!).

Drawing with the mouse was laborious. But when we presented images to Stern and GEO magazines they were mesmerized and published features about the compost heap and medicinal herbs. This was 1997 – our breakthrough year – when we gained public recognition.

As a partnership how do you organise the work flow?

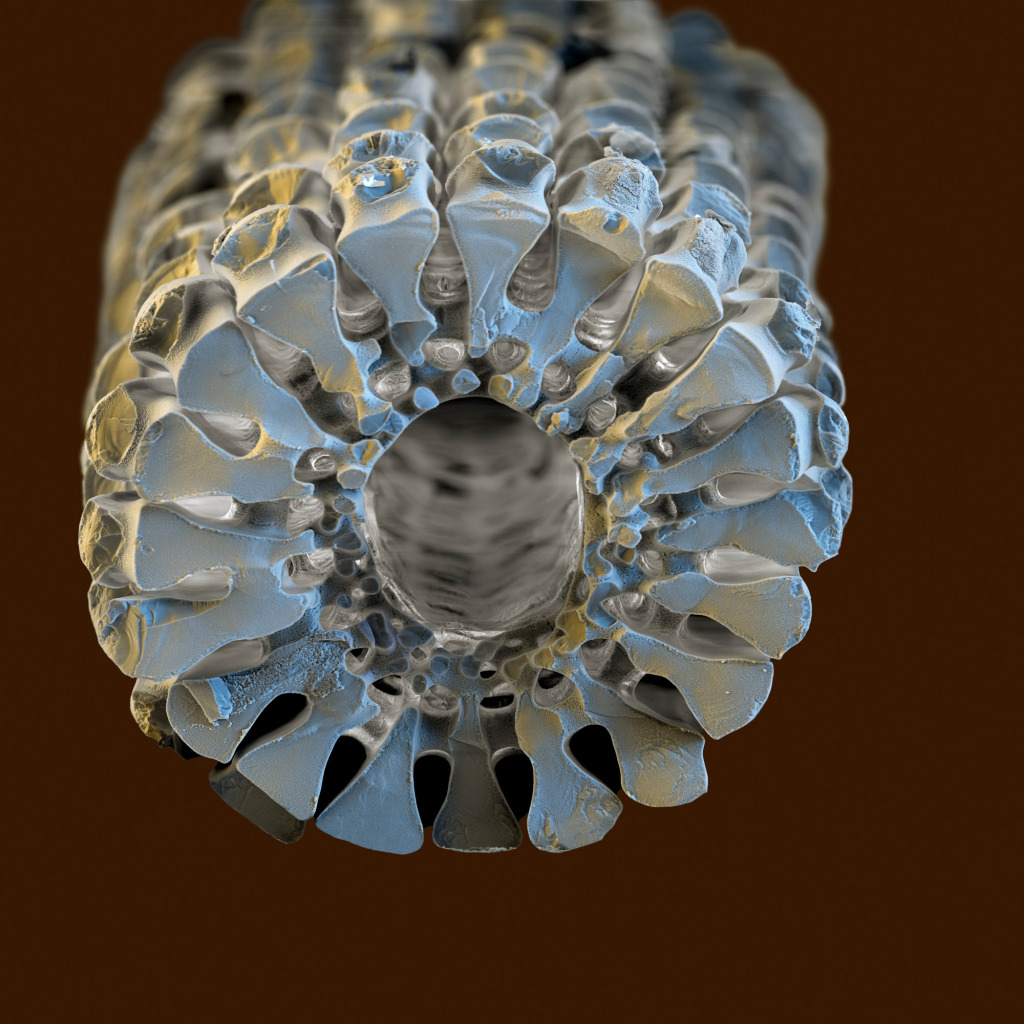

OLIVER & NICOLE: Oliver makes most of the SEM specimen preparations, which means fixing, dehydrating and drying the specimens as well as mounting or arranging the tiny samples on the specimen holder (12mm in diameter).

We both operate the SEM and do digital imaging about half and half. Oliver as the photographer makes the last adjustments to the images. The least loved work, writing image captions, is also shared between us.

What persuaded you to pursue the unusual career of freelance SEM microscopists?

OLIVER & NICOLE: Indeed, it’s unusual. Once fascinated by the worlds within worlds, what could be better to do all day long!? It was a financial risk, so Nicole started a part time job in a hospital laboratory to pay the rent. Oliver contemplated driving a taxi at night if the dream didn’t come true soon. But as mentioned, with the stories in GEO and Stern we made it after two years and Nicole quit her job at the laboratory.

Oliver did not need to drive a taxi.

What is it about the SEM in particular that holds your fascination?

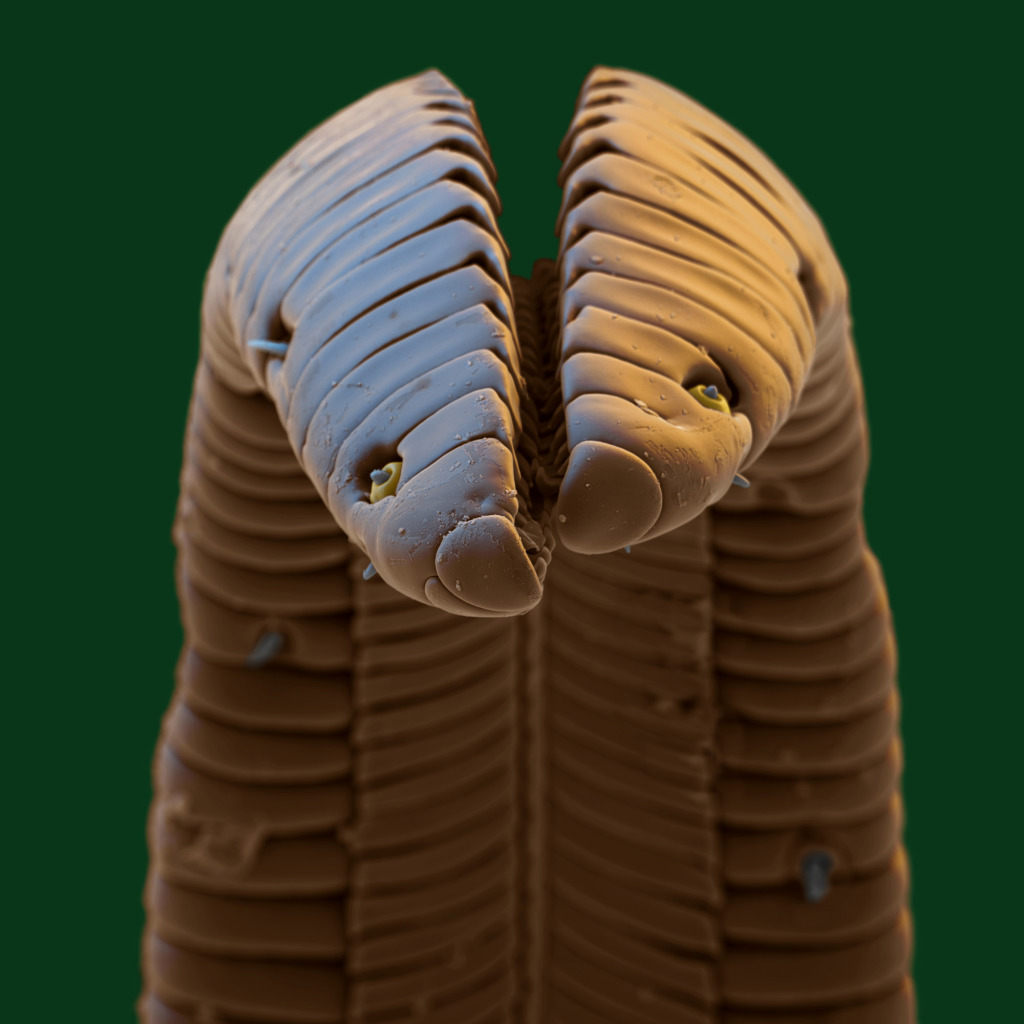

OLIVER & NICOLE: Every day you might see something nobody has seen before. And what you might discover is very often unexpected: even in the smallest things you might find amazing detail and beauty.

A great deal of your work is done on commission. What sort of clients do you work with and is it a reliable market?

OLIVER & NICOLE: Unfortunately there are not too many clients interested in this kind of imagery anymore. But over the years there were several clients from the pharmaceutical, chemical and medical industry who wanted us to make their calendars (big sized 27”x20”) or images for advertising and annual reports. Since the financial breakdown in 2008 there is a gap there.

One of the aspects of your work that stands out is your colouring technique. What is it that makes yours so different?

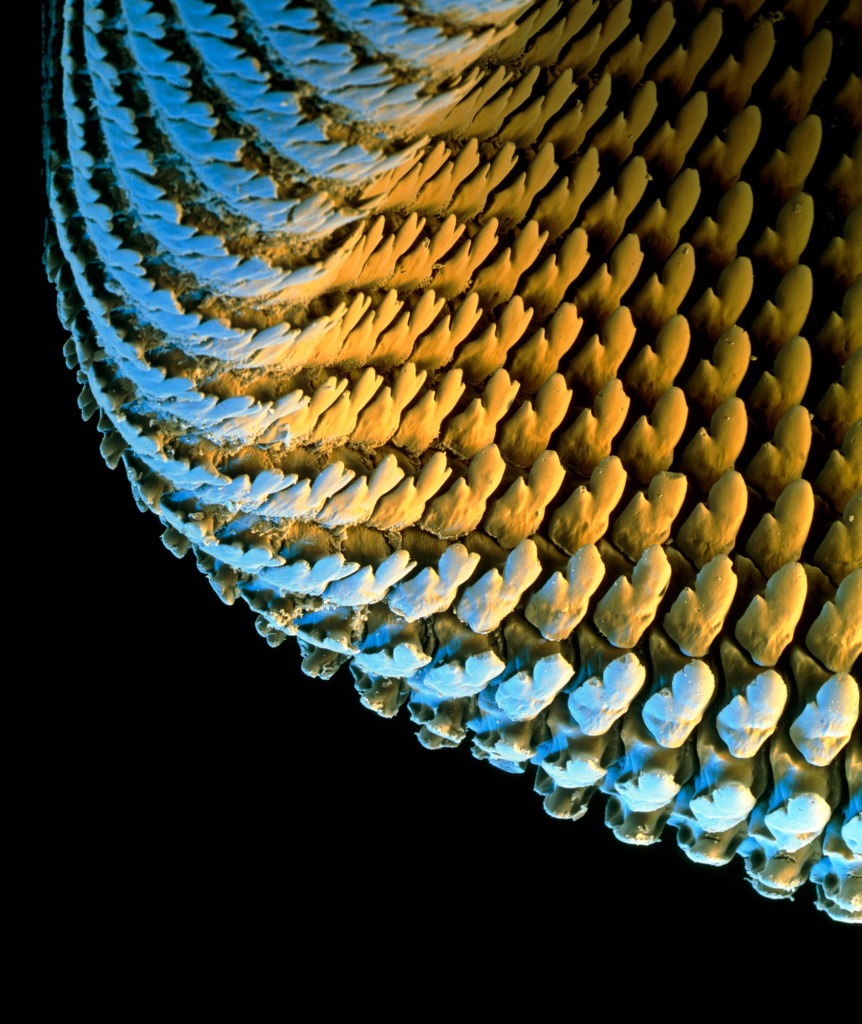

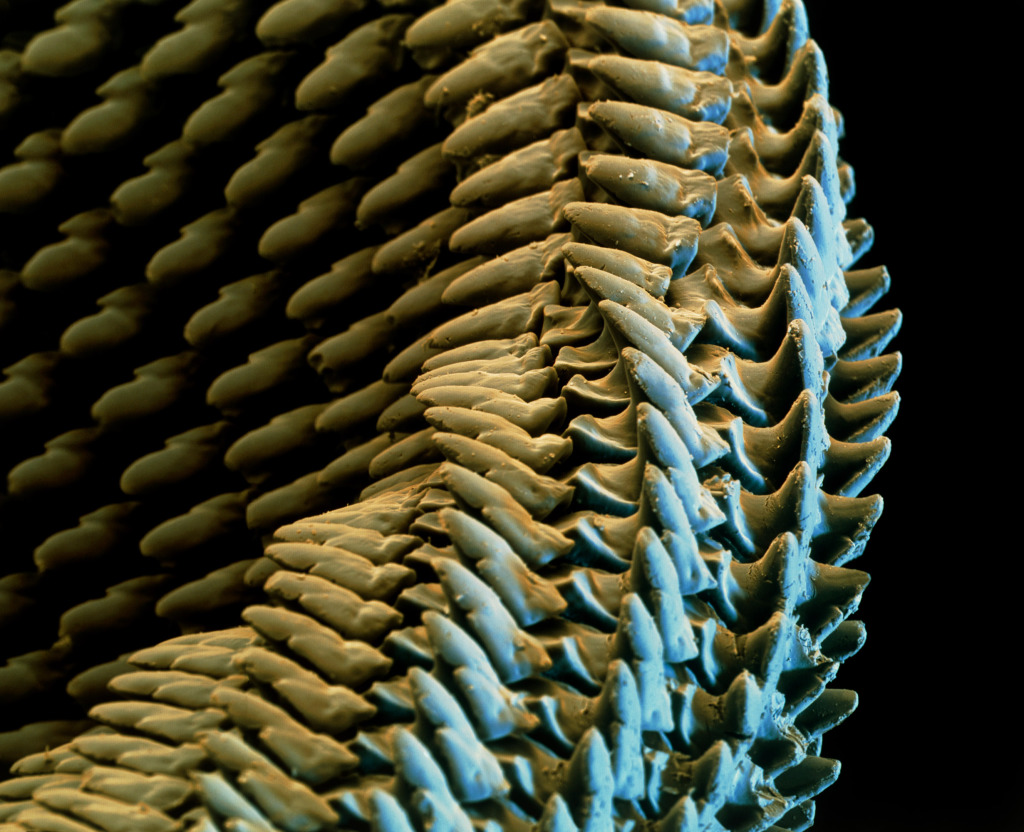

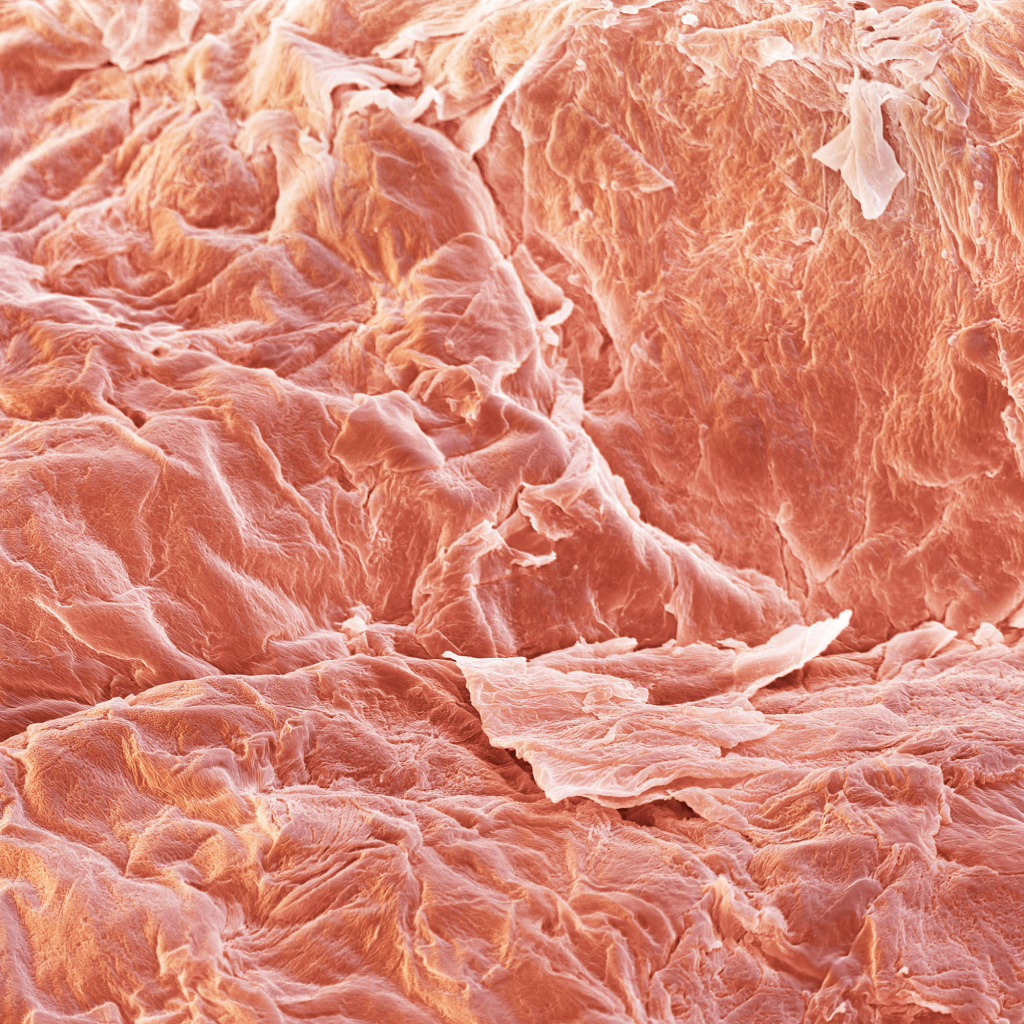

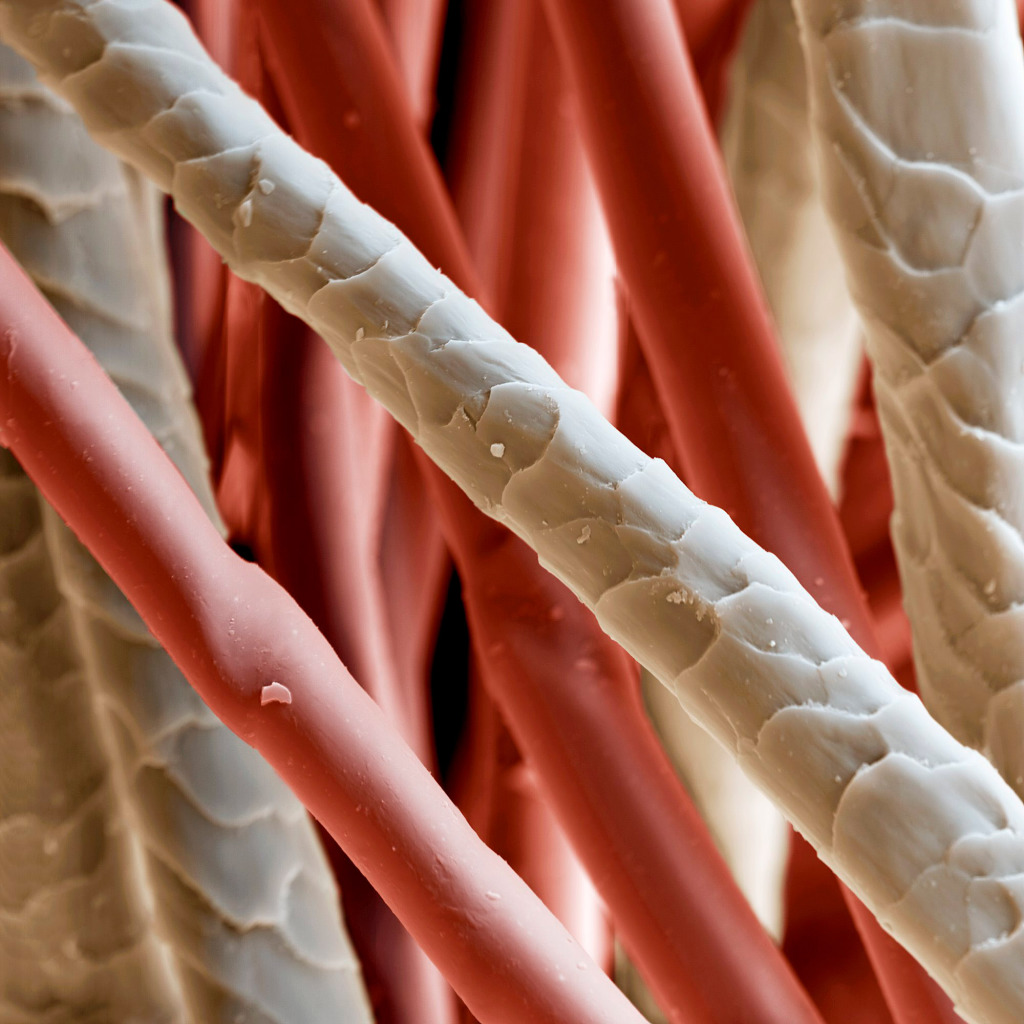

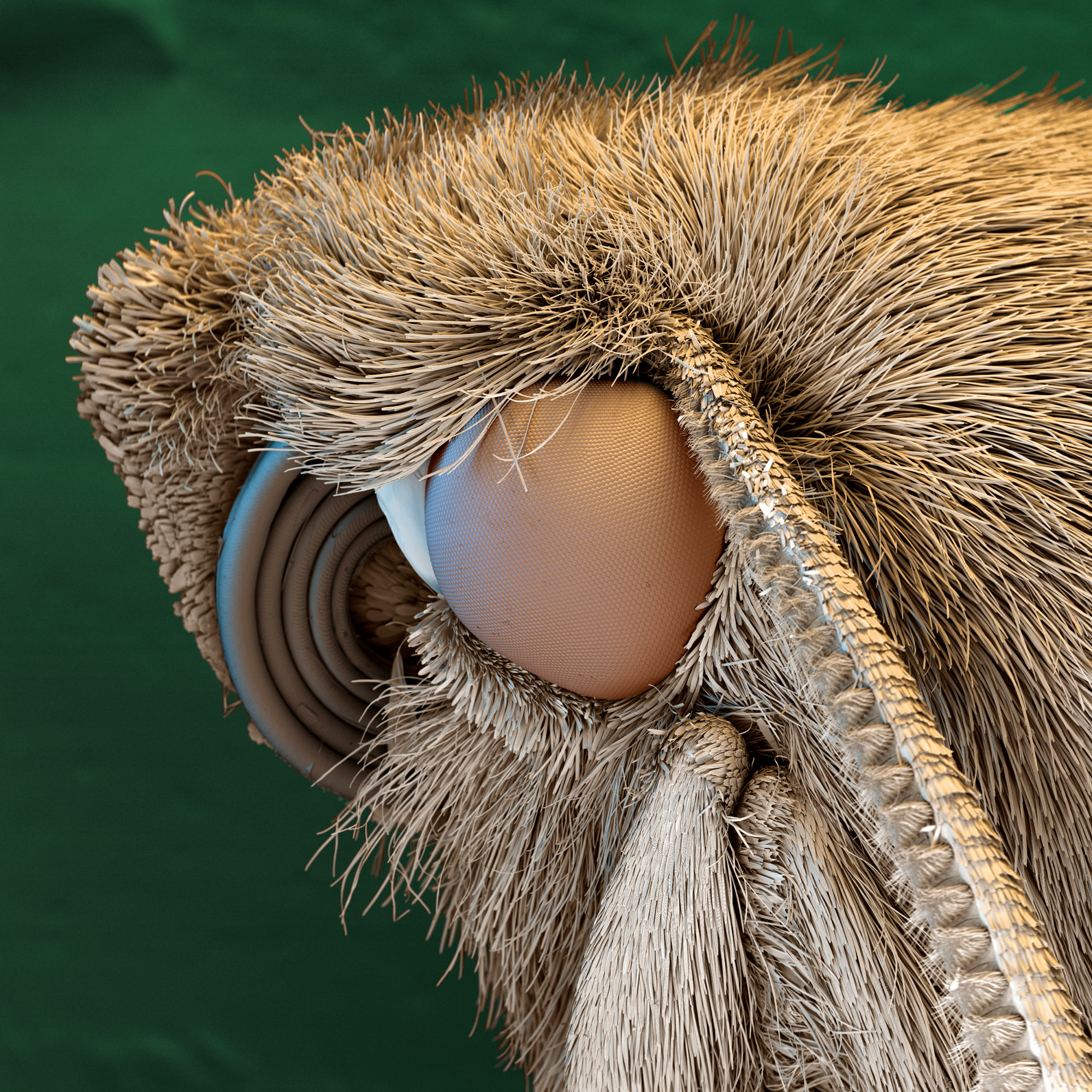

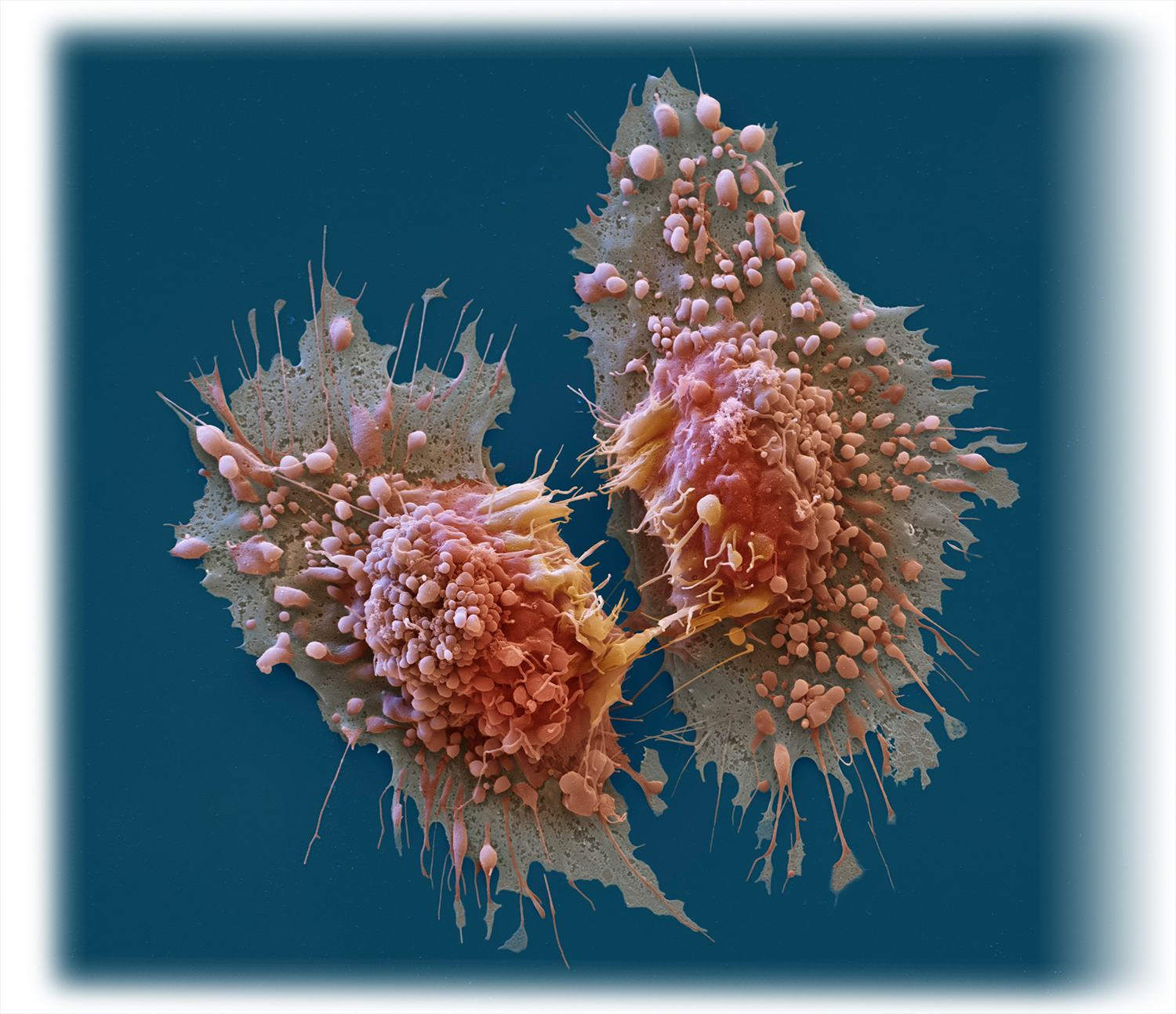

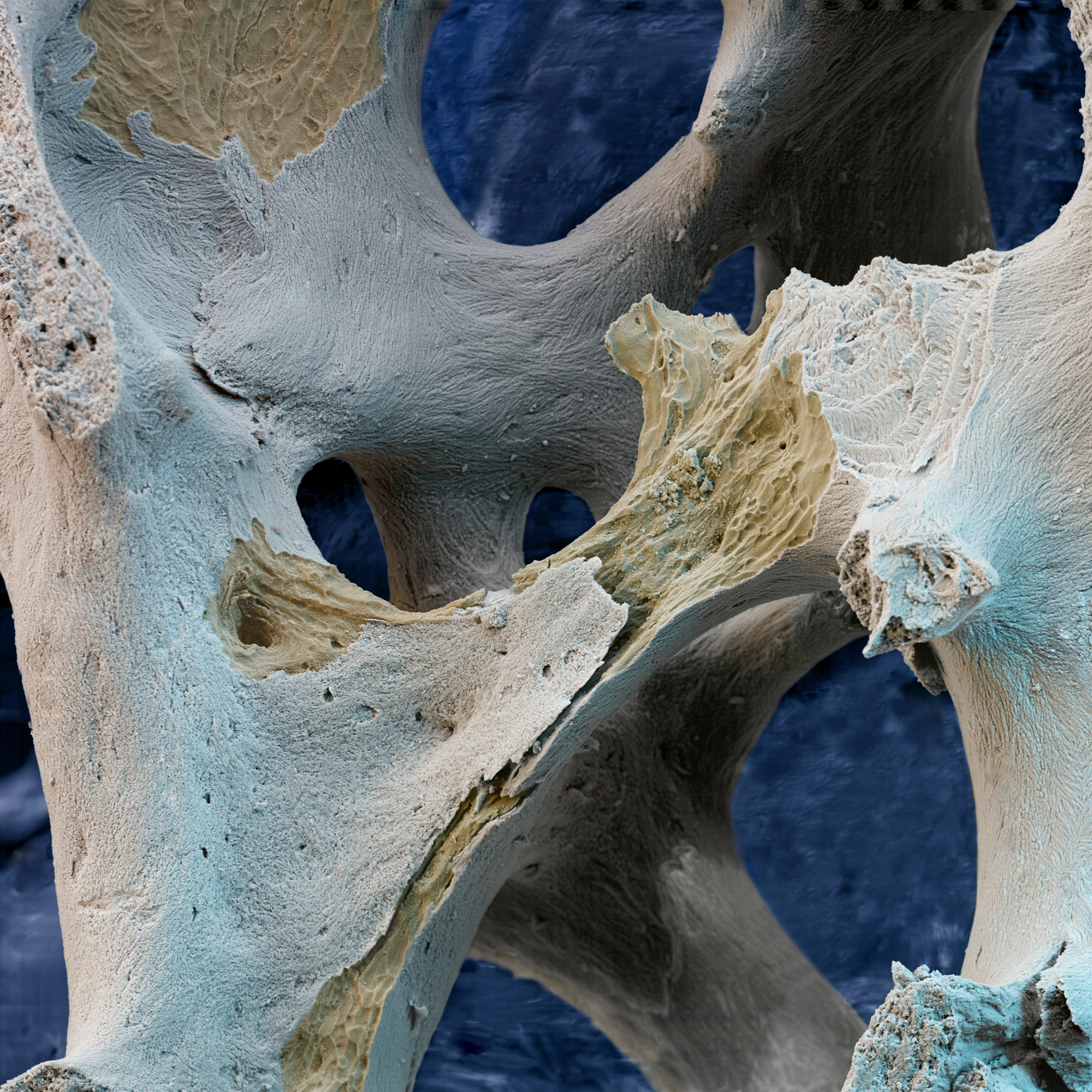

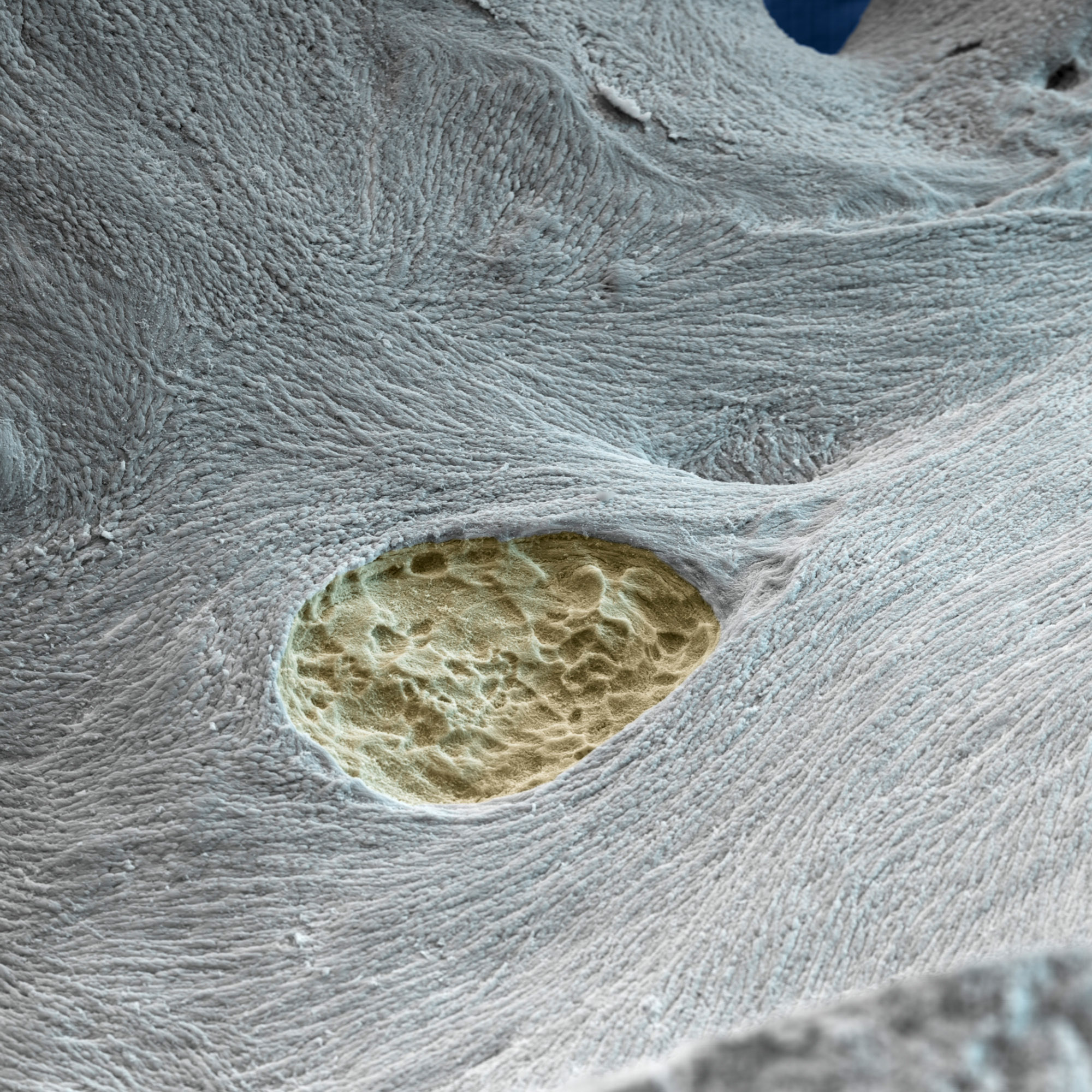

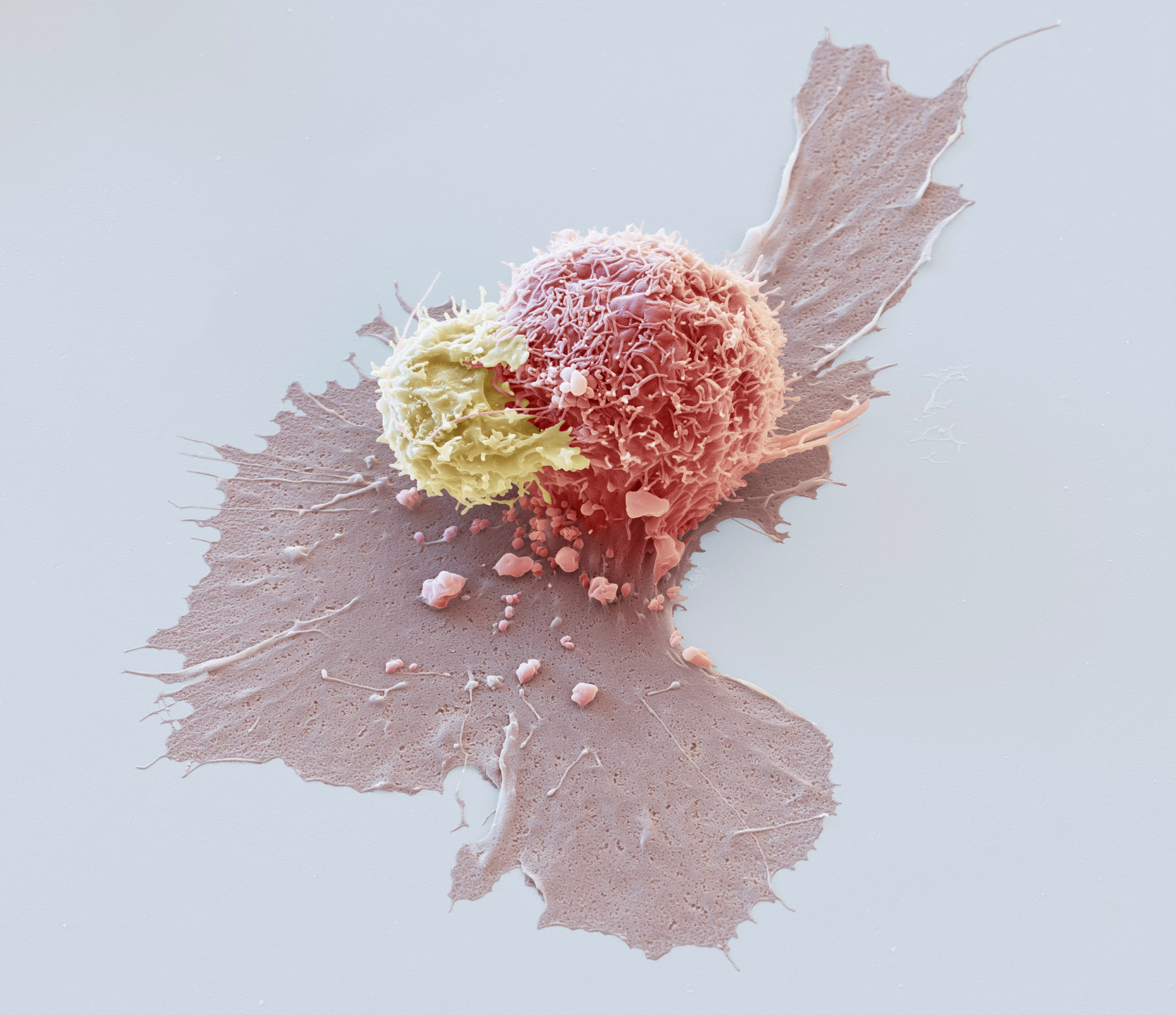

OLIVER & NICOLE: Most SEM specialists are technically trained as microscopists not photographers. They look at the specimen for what is important, no matter from which angle or in which illumination. Facts count. As photographers, we look differently. First, we search for the best representative area, then we look for the best imaging angle and finally ask ourselves does the ‘light’ fit. This is our speciality.

The SEM doesn’t use light to produce an image it uses electrons. We position detectors in a way that mimics the effects of light, making the specimen appear to be backlit or caught in a spotlight. It creates a naturalistic lighting environment and enhances the 3D effects of SEM images. The original black and white image is then coloured in Photoshop. It is a lot of hard work!

Why do you think SEM imagery is so popular with the public?

It’s a fascinating unseen world and

somehow hyper-realistic.

Tell us about the most challenging image you have had to produce?

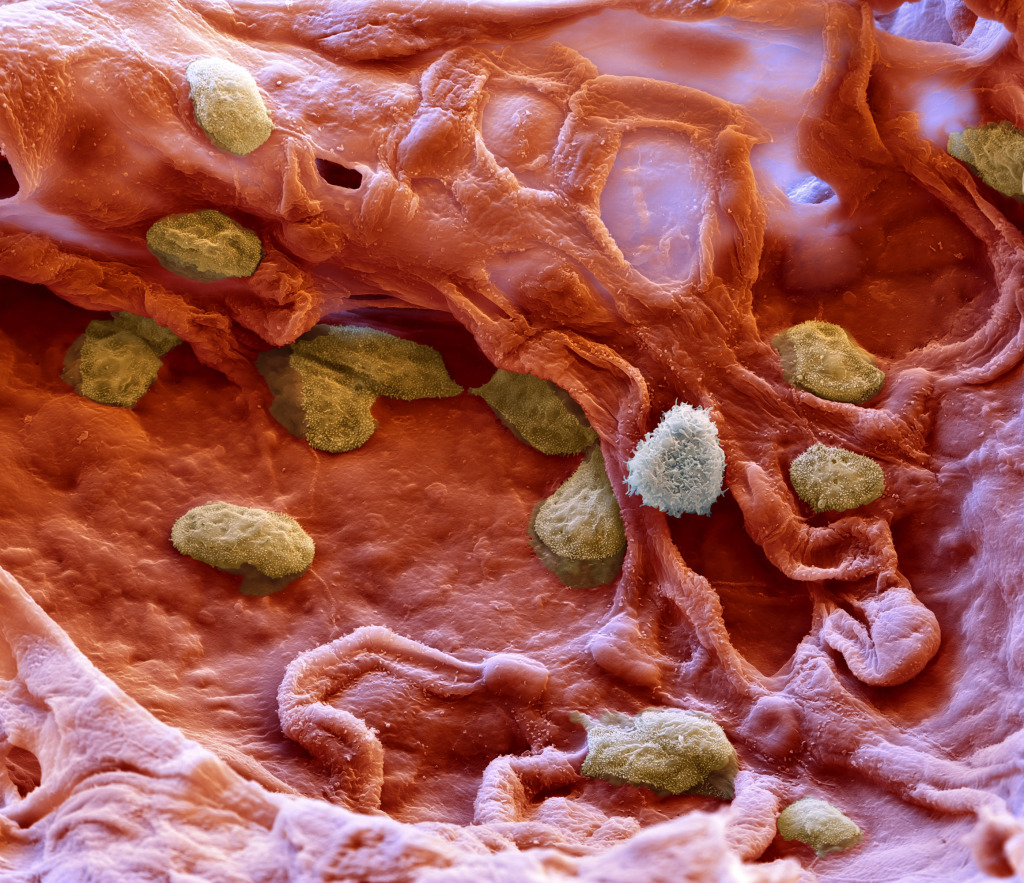

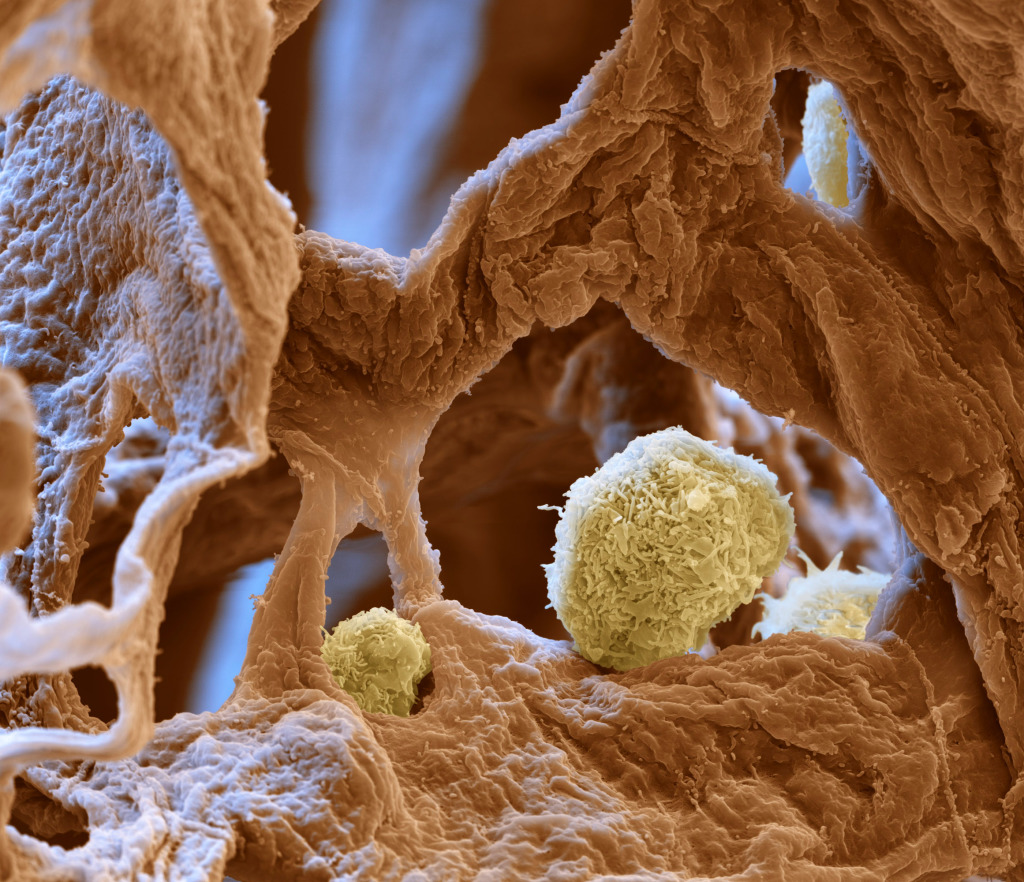

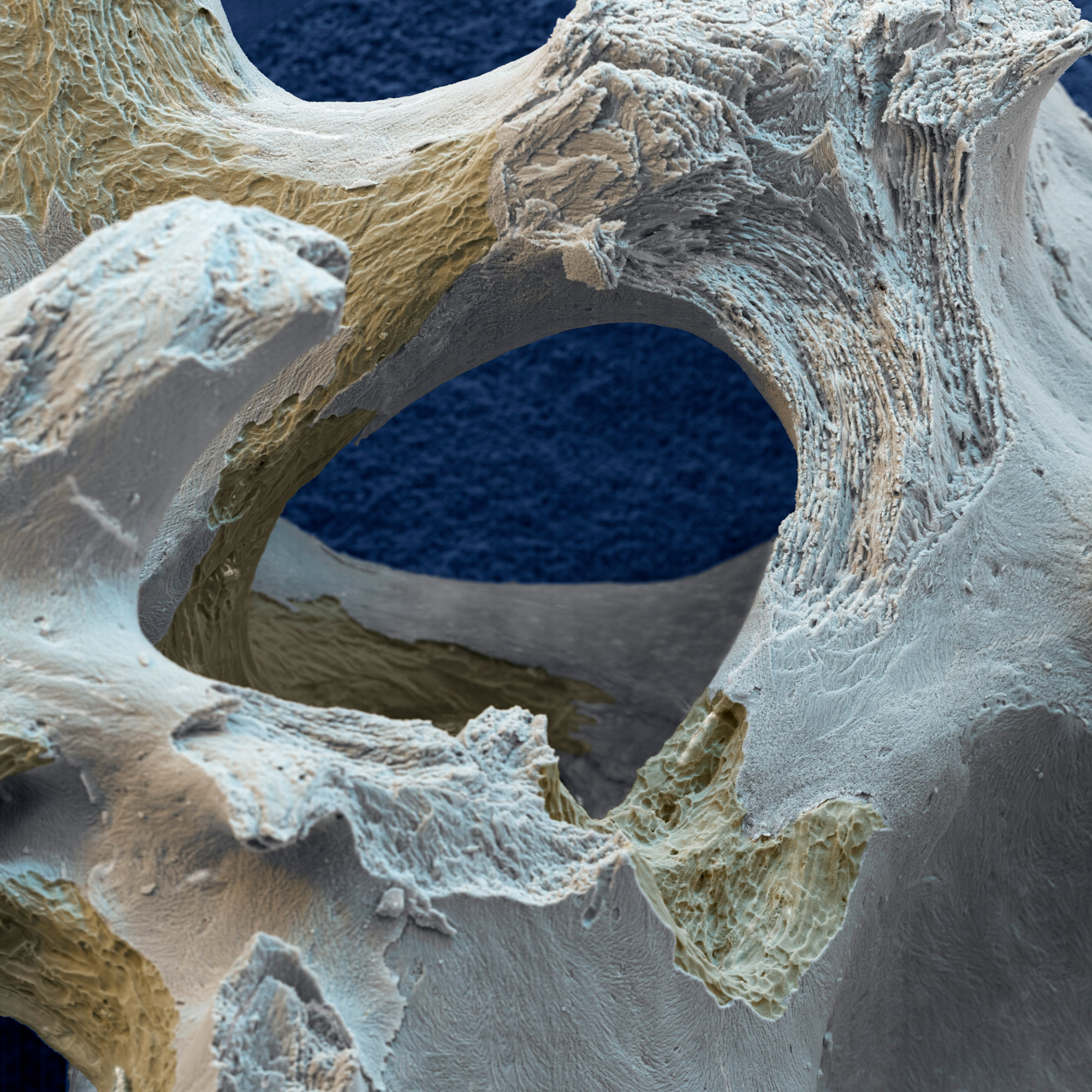

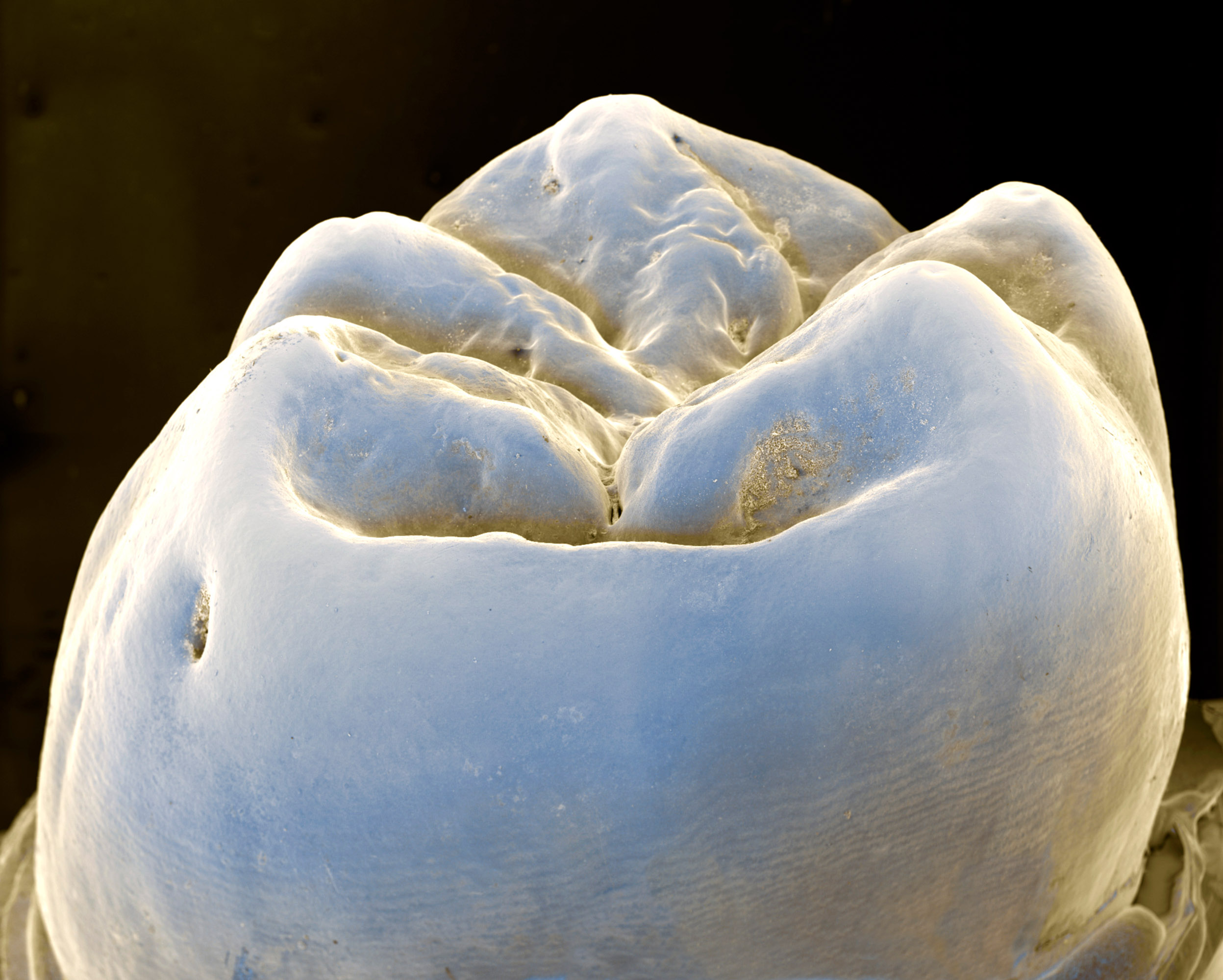

OLIVER & NICOLE: Haha, there are a lot. Can you imagine putting the freshly removed molar tooth of your son into liquid propane to make a freeze-fracture preparation? After freezing and cracking it was put into Osmium-tetroxide solution, dehydrated, CPD dried and Palladium coated to get an image of the tooth-supporting cells, the odontoblasts. Or mounting a single pollen grain on a semiconductor sample as a size comparison?

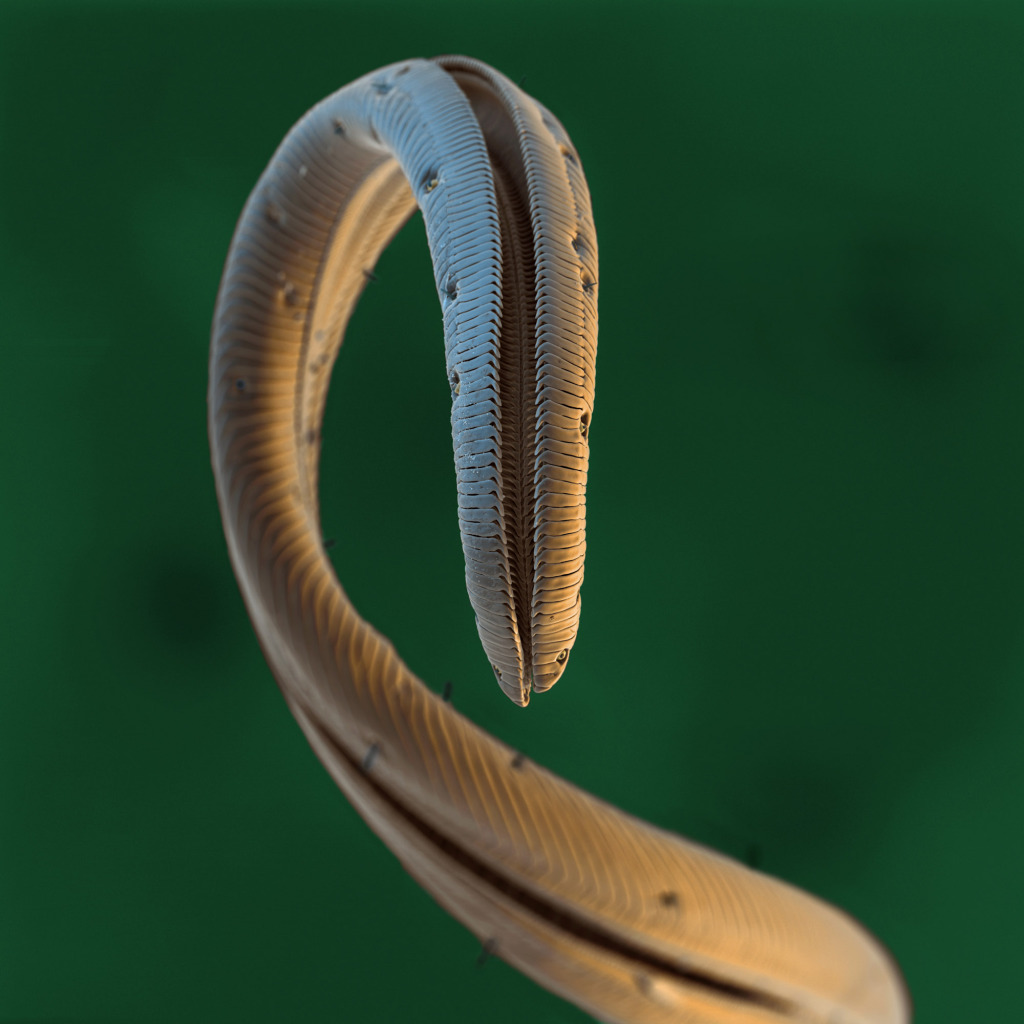

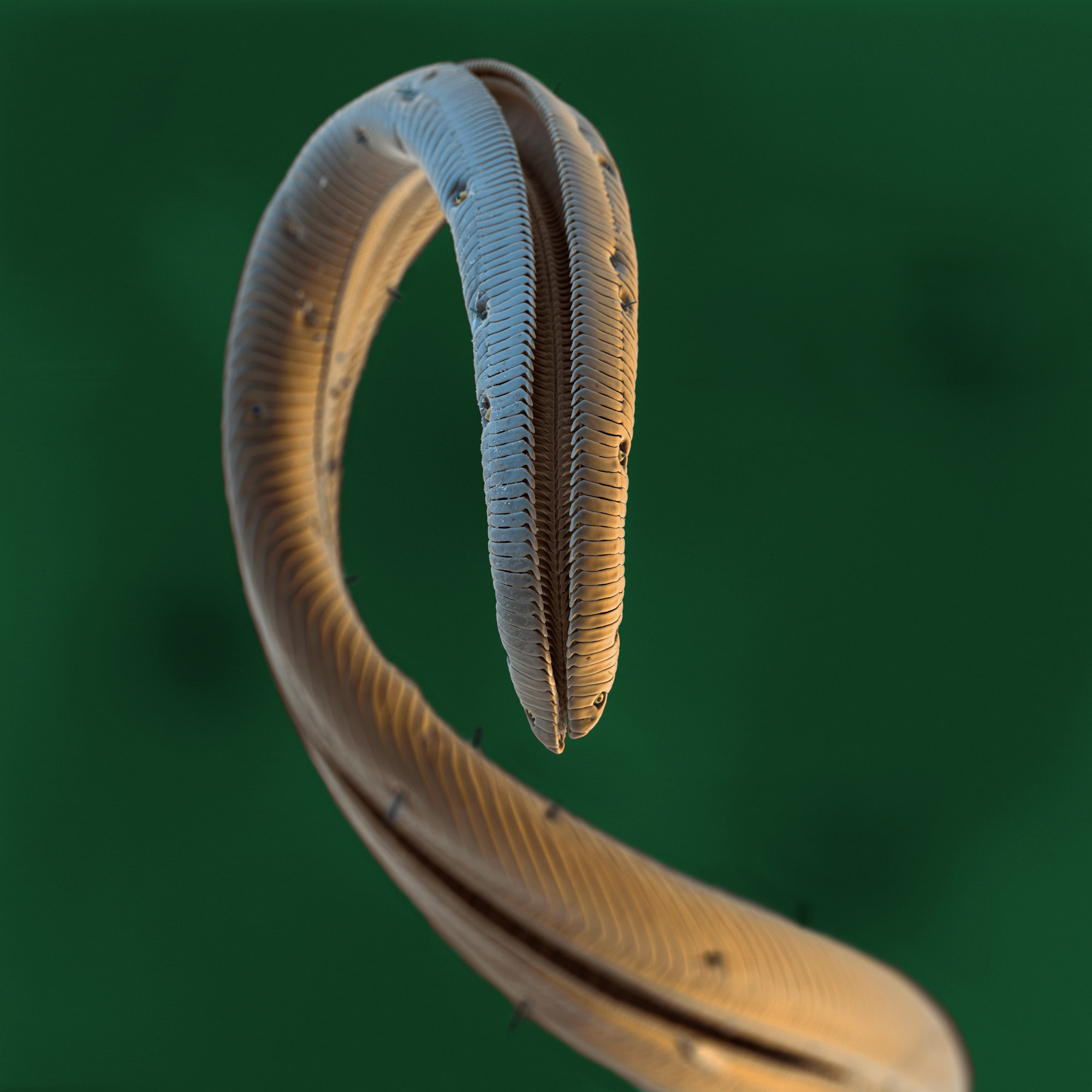

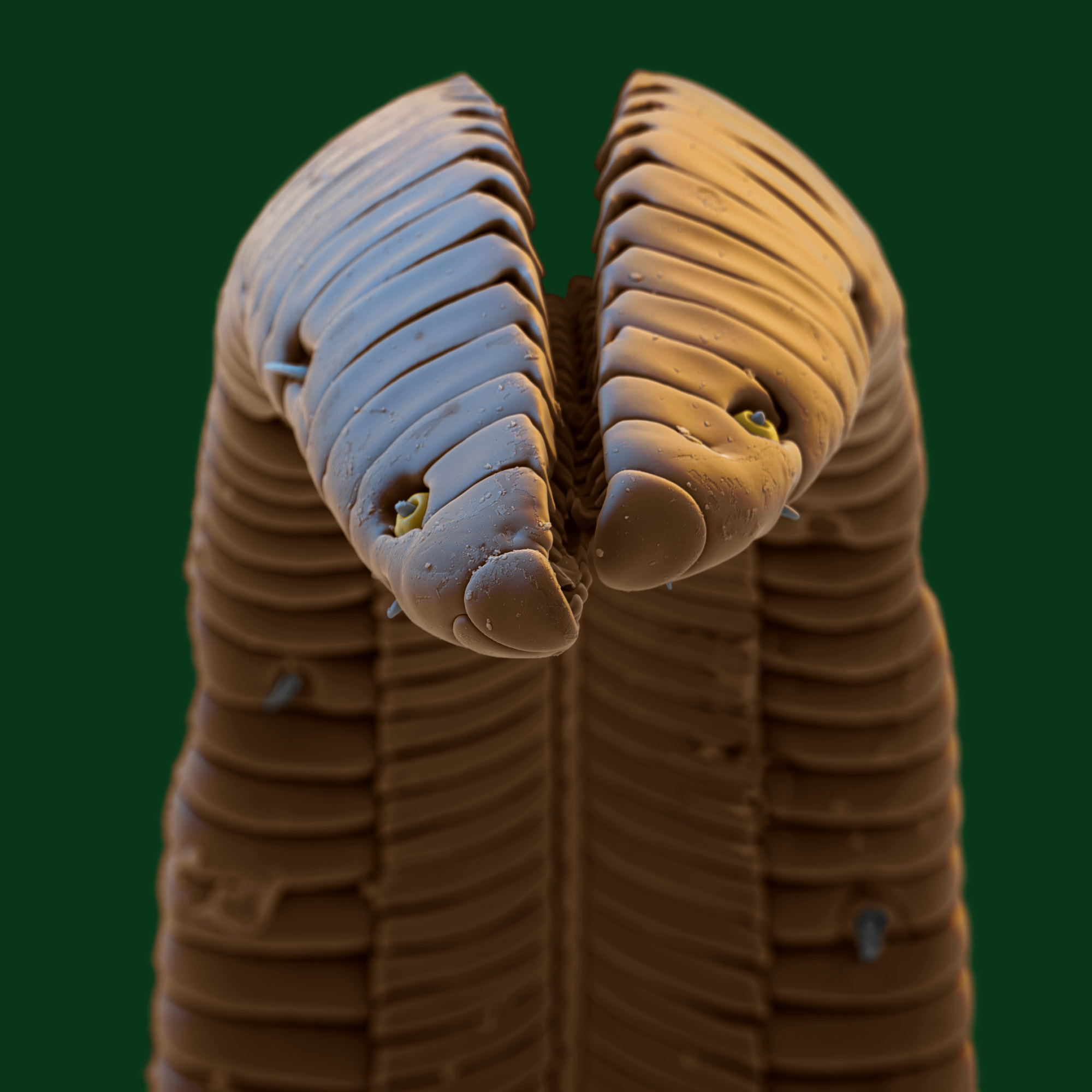

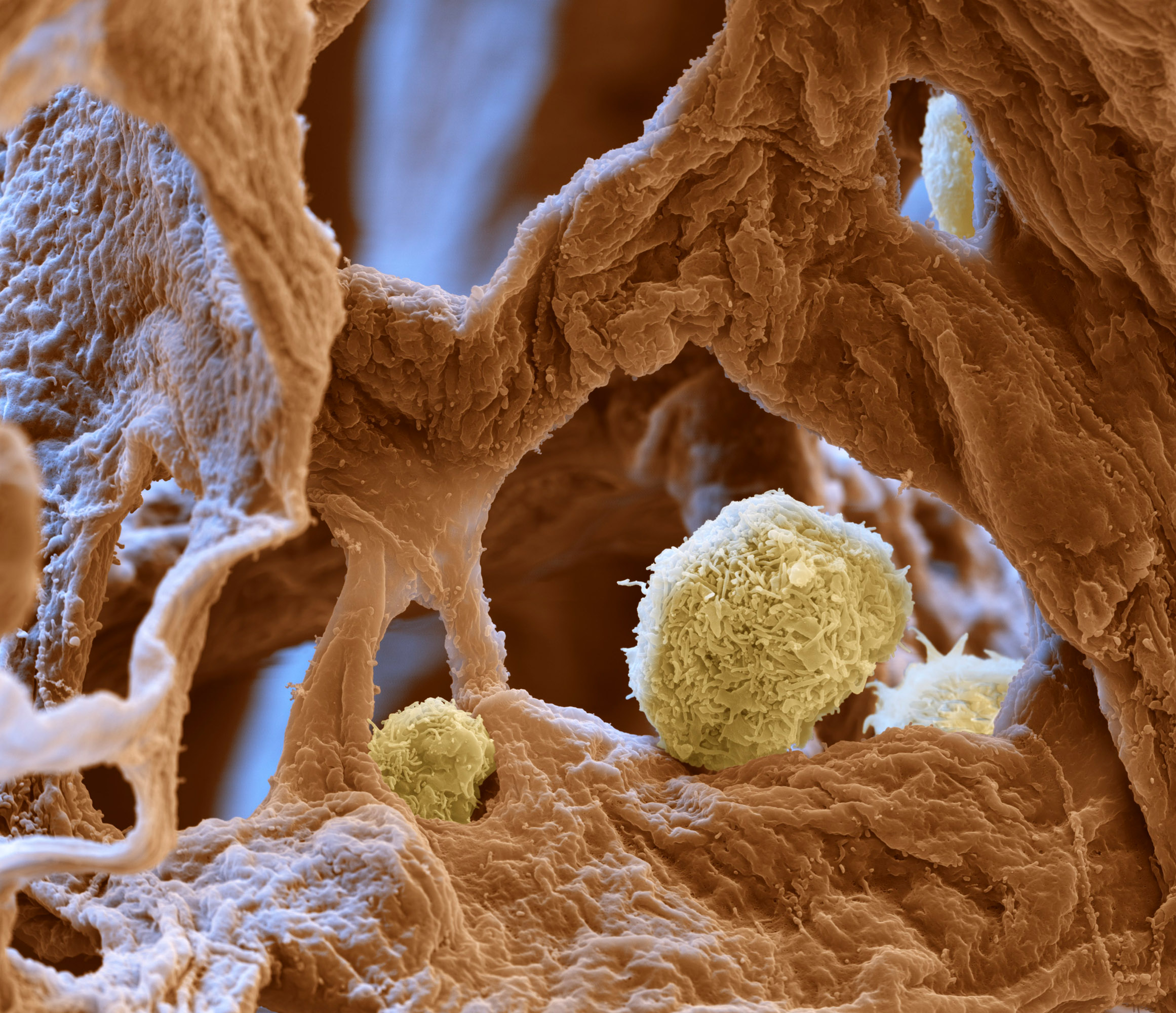

You know, there are ‘dioramas’ in museums, displays in glass fronted cabinets that show a stuffed lion and an antelope in their natural habitat. That’s what we did with 0.1mm small mites. After the total exsiccation (drying) and metal coating process we placed them on a piece of wood together with nematodes, springtails and moss – we created a diorama of mites from the microscopic world.

The technology has developed significantly since the 1990s. How do you see future changes affecting your work?

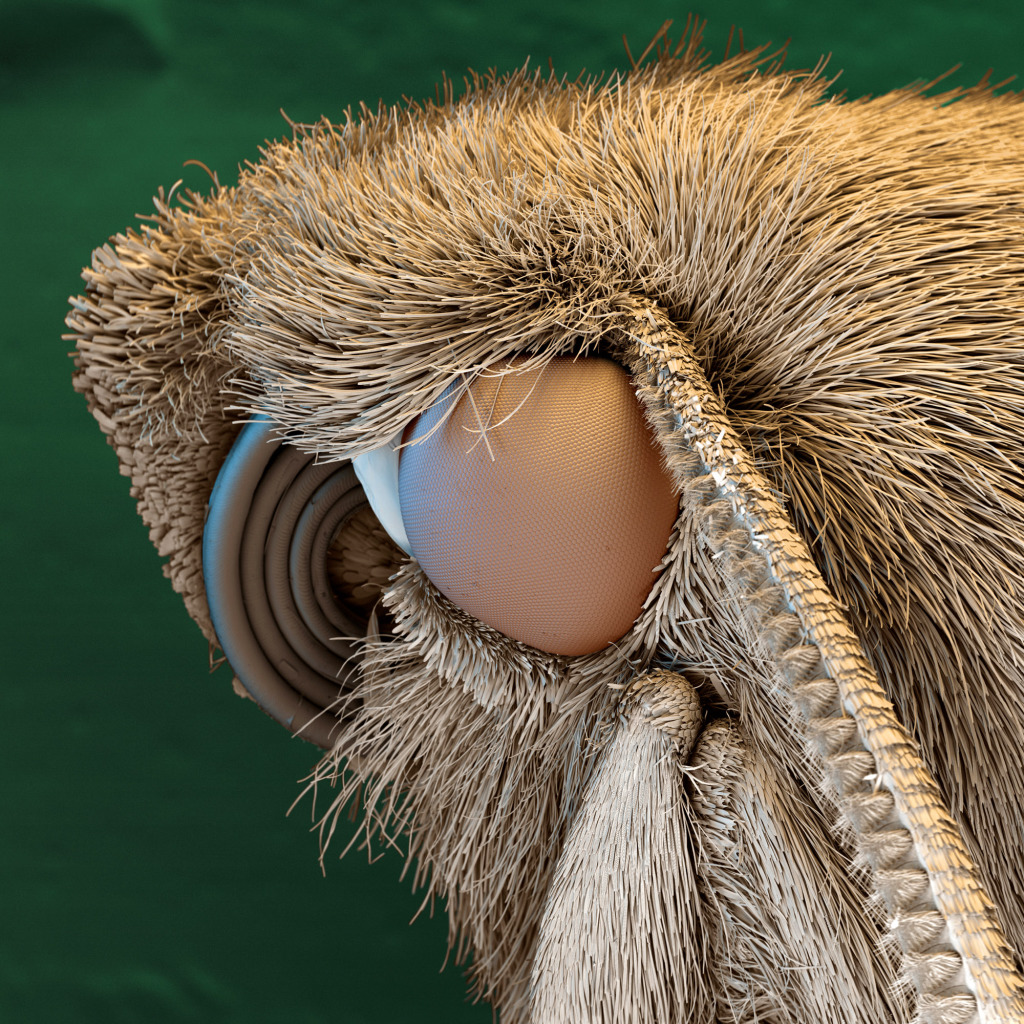

OLIVER & NICOLE: The future already affects our work. Our business suffers from competition with 3D renderings that look like SEM images. They can be done cheaper and faster than SEM preparation and imaging, but what these pictures show is not the “image” of something. These renderings are artworks and sometimes pure fantasy sold as science. That’s one problem of our fast, digital world. All is fast and cheap, authenticity is not important. Things have to look amazing, be an eye-catcher and must be new every day. Reality often gets lost. Who cares?

On the scientific side microscope techniques have developed rapidly. Confocal light microscopy broke the physical barrier of resolution by 20x, dye techniques can selectively colour cells based on their properties or mark just big molecules! Digitized microscopes are able to scan full specimen (20x20mm) and store them as one file to zoom in like google maps, from 1:1 to 1000:1 in one image.

Computer tomography (CT) known mainly in the medical arena also has captured the microworld, imaging insects on a cellular level in micrometre resolution. In the last 10 years there has been an explosion of microscope technologies with no end in sight to the possibilities of seeing in new and exciting ways.

25 years ago we started Eye of Science using the SEM, a new and revolutionary state of the art technology which now already appears to be somehow old fashioned. But with 25 years of experience, we continue to find new and hidden parts of our reality bringing them into the best possible spotlight!