Mark creates an entire universe that you can immerse yourself in. Discover a new way to experience art.

Mark Garlick

Science and imagination

When did you first become interested in space and astronomy; was it a childhood fascination?

Yes. I was drawn to the subject primarily because I liked the artist’s impressions that filled astronomy books – illustrations by people whom I now count among my colleagues. The illustrations got me hooked on astronomy, and it was natural for me to then study it at university.

What was it about these subjects that appealed to you?

The vastness of it all; the incredible sense of scale; the unknown; the beauty and wonder in the images.

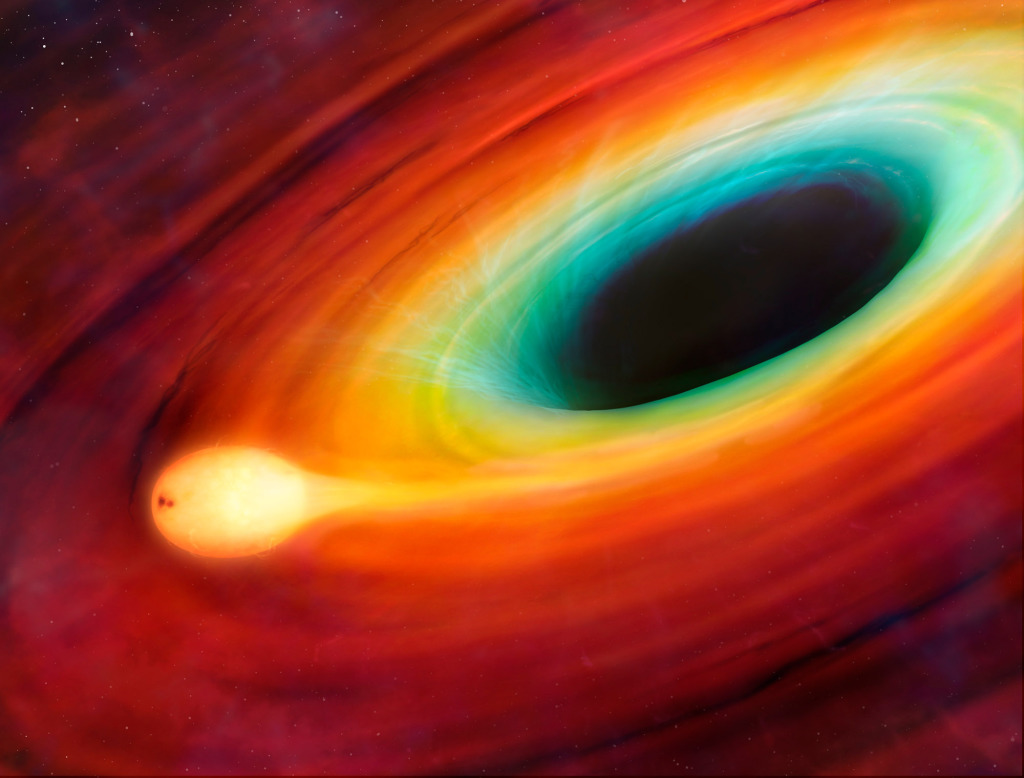

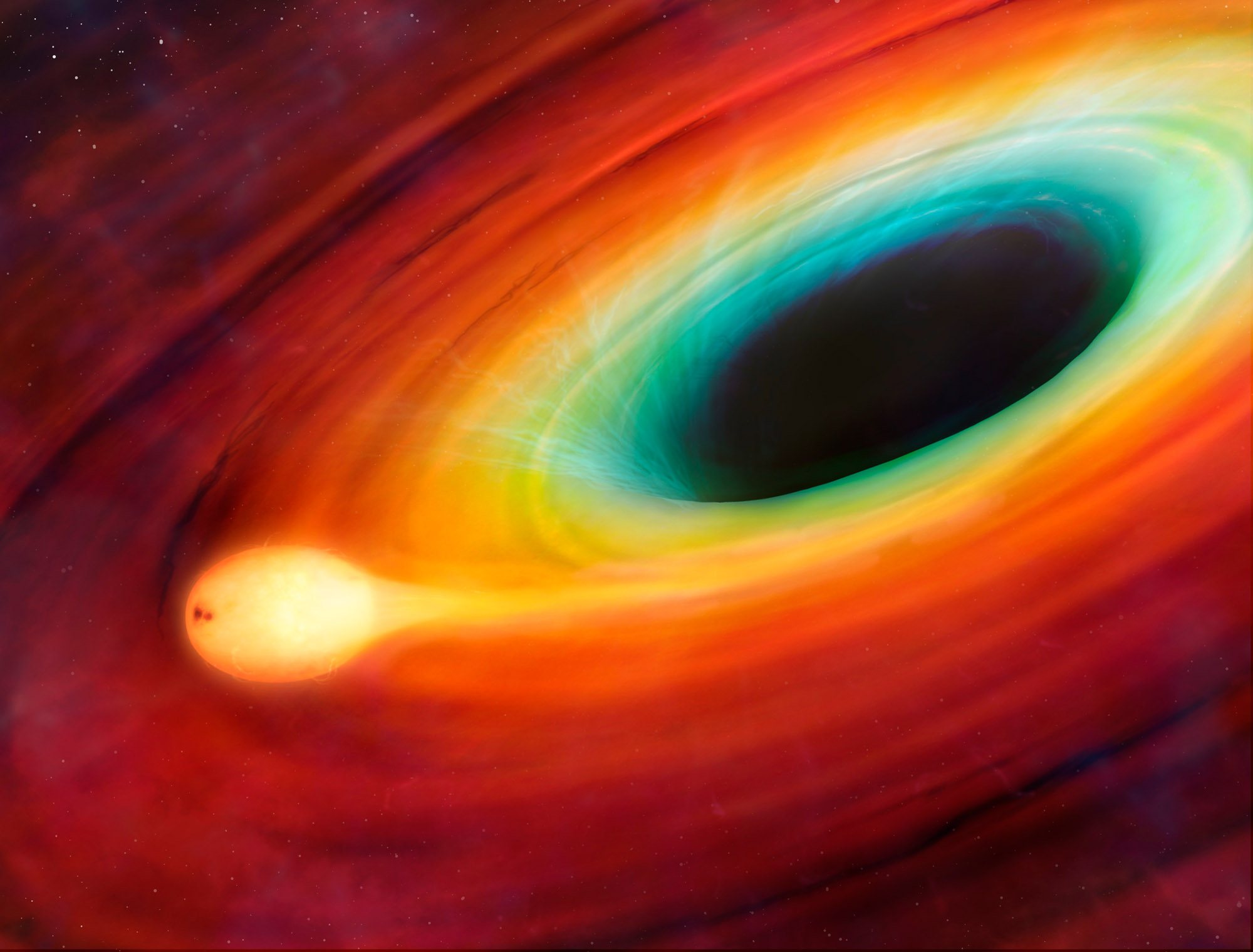

Relativity especially really struck a chord with me. It is all so counter-intuitive and yet it does accurately depict our universe, our reality.

I found it fascinating, and still do, that time can run at different rates depending on how fast one is moving, or how close one is to an intense gravitational field.

You gained a degree in astrophysics and held a research position in theoretical astronomy at the University of Sussex. What led you to change direction and become a graphic artist?

At school, I was always good at art. I did my O Level a year early and my A-Level the following year – two years early. But when I decided to go to university, I didn’t want to carry on with art. I was a bit fed up with it all. It seemed natural at the time for me to study astronomy, so that’s what I did. I did a bachelor’s degree and PhD at UCL, and postdoctoral work at Sussex University before I decided that this was not the direction I wanted to go in either!

I had in the meantime rekindled my interest in art. I was painting (in acrylic) in my spare time and was dabbling in space art. I also realised that I quite liked writing – penning my thesis had brought this out in me. So when my postdoctoral research contract came to an end, I decided to have a go at freelancing as an illustrator and writer, specialising (at first) in space and astronomy. Once I adopted digital art in 1998, I suddenly became much more prolific and my career as an illustrator took off.

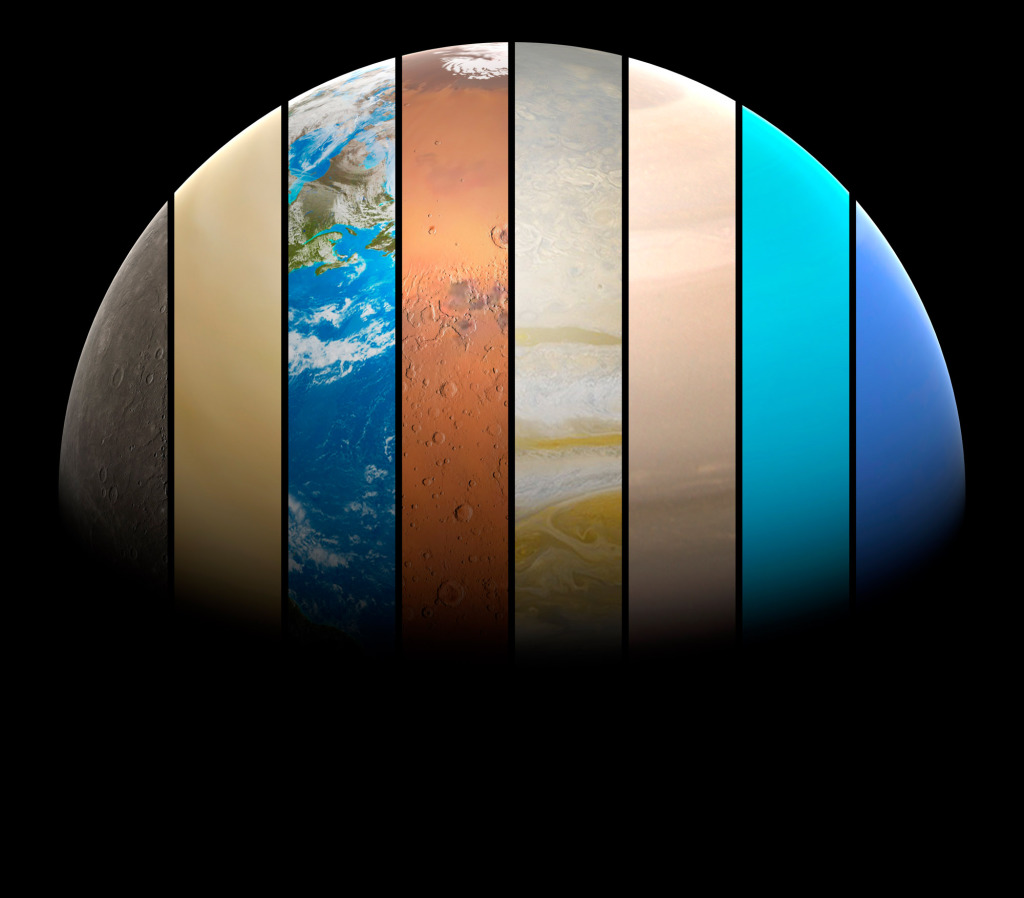

Shortly after, Cambridge University Press published my first book, which I conceived, wrote and illustrated. It’s called The Story of the Solar System. It was great the way my scientific training and my interests in art and the written word merged in the end.

When you are given an idea to illustrate what is the balance between science and imagination in the final image?

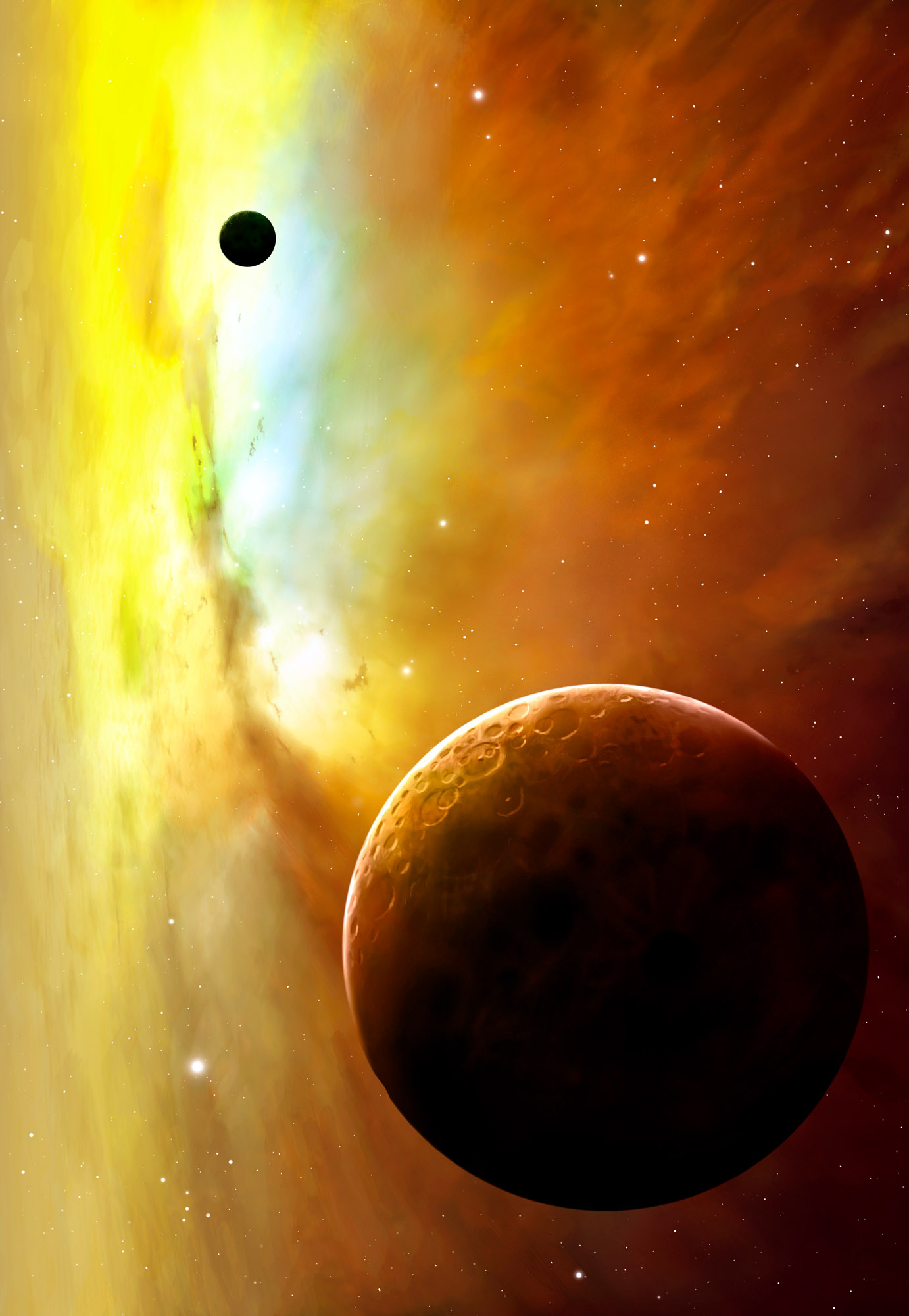

It depends on the image. Some of my work is pure imagination, but most is based on real science. It is difficult to depict space without bending a few rules, though. For example, a nebula seen up close from the surface of an alien planet, say, would be practically invisible. The nebula only looks bright when it’s small and seen from a distance. Cameras can integrate light – the longer the shutter is left open, the brighter the exposed image. Our eyes cannot do this. So up close, the light from a nebula is diluted over such a vast area that it would be hard to see. We have to ignore this if we want to create a scene of a nebula or galaxy filling an alien night sky.

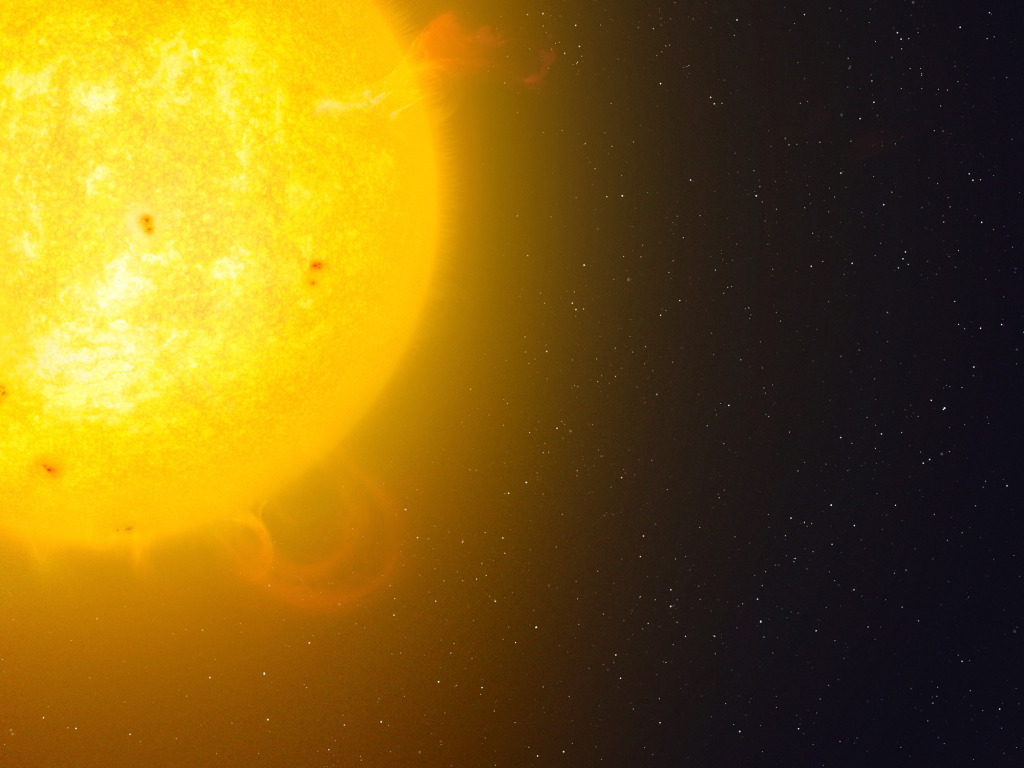

Stars are also tricky – impossible, really – to depict accurately. Imagine how bright the Sun is on a summer’s day. It’s impossible to look at. If you photograph it, either the foreground is dark to properly expose the Sun, or the Sun is heavily overexposed to correctly bring out the foreground. Now imagine trying to picture a red giant star – thousands or tens of thousands of times brighter than the Sun. To create an artwork showing such a star filling the sky of an alien planet, the artist has to ‘expose’ both the foreground and the sky properly, the way that a camera cannot. You have to imagine, almost, the scene as viewed in a camera with a vastly expanded dynamic range.

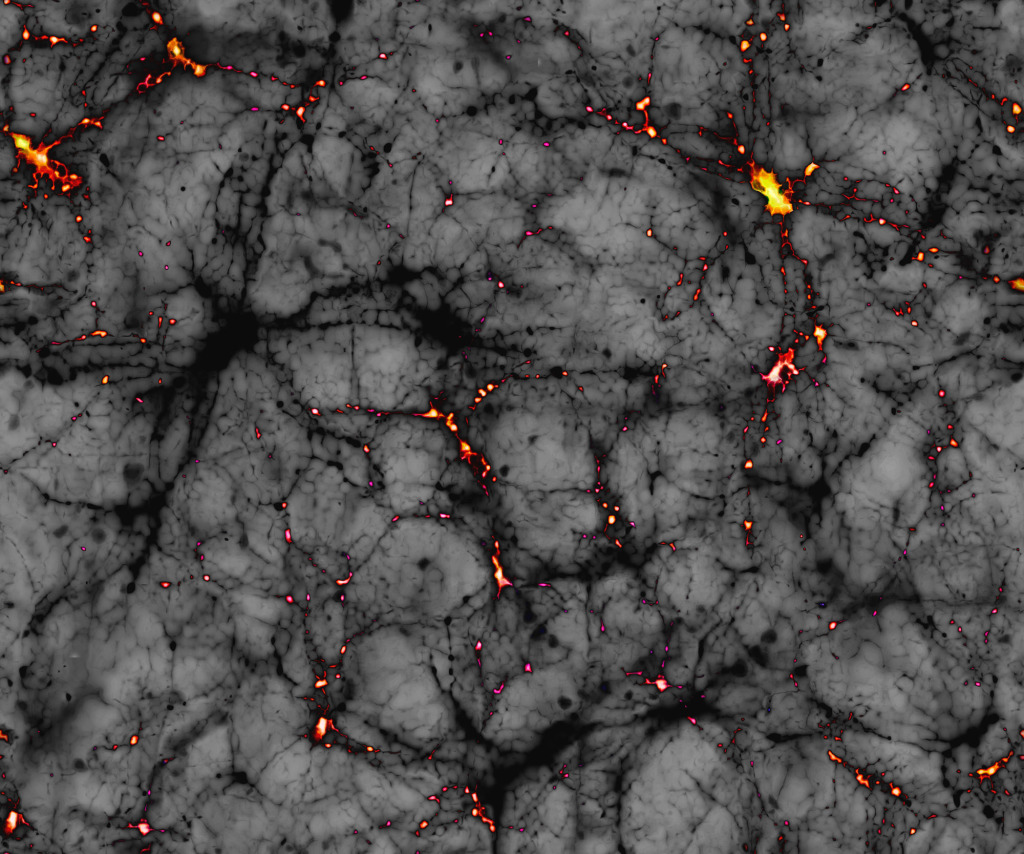

Your portfolio has expanded to include physics and evolution. Was this a natural progression?

Yes, pretty much. I see what kinds of work SPL has in its collection and, if I can do similar work, I do.

Dinosaurs were another of my childhood loves, so it was only natural that I’d end up depicting them too.

Where does your commissioned work come from?

Originally it used to be mostly books and magazines – editorial work. Sadly this is becoming rare. Although I do get the odd magazine commission (recently from National Geographic), they mostly use in-house artists or stock illustrations.

More and more, my work comes from TV companies (animations for documentaries) and academics (illustrations and animations for press releases).

You’ve recently begun producing animations. What new challenges do you encounter?

It’s not that recent anymore – my first animation (of a binary star) was in 2009!

The main challenge, beyond learning how to use the software (3DS Max, then Blender), was finding a way to make the scenes look photorealistic without much post-production. Before I did animation work, I used 3D sparingly. I’d create an image in 3DS Max, and then work on it in Photoshop to bring it to life.

For animations, it has to look pretty good straight out of the renderer, as post-production options are much more limited than with stills. Another challenge comes from hardware limitations. I need a much higher specification machine to create animations than I do for stills.

Where do you find inspiration to illustrate your ideas? Who are your artistic influences?

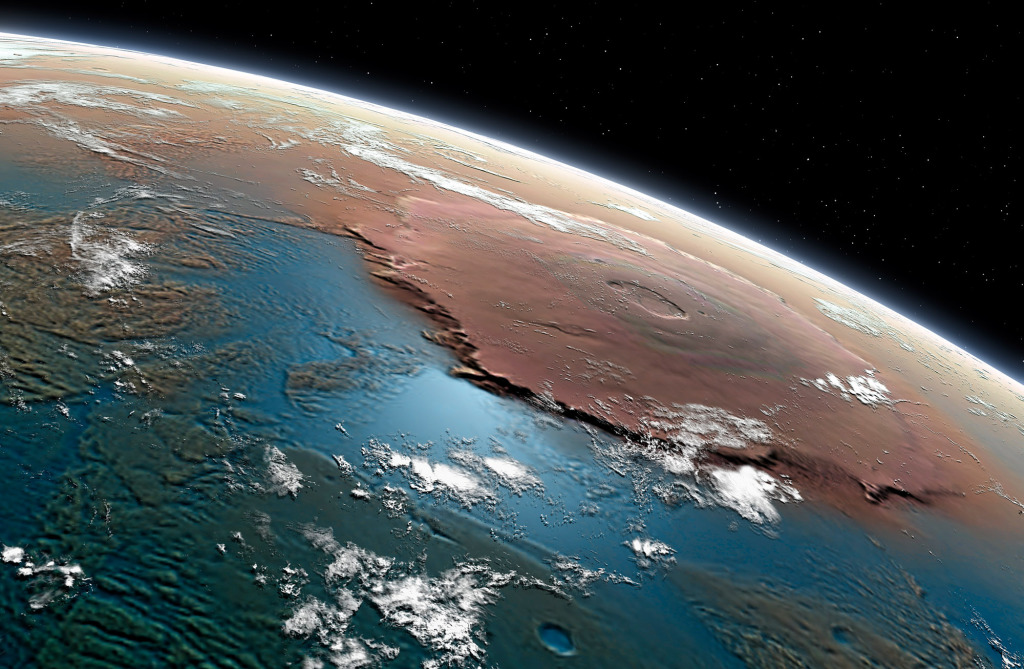

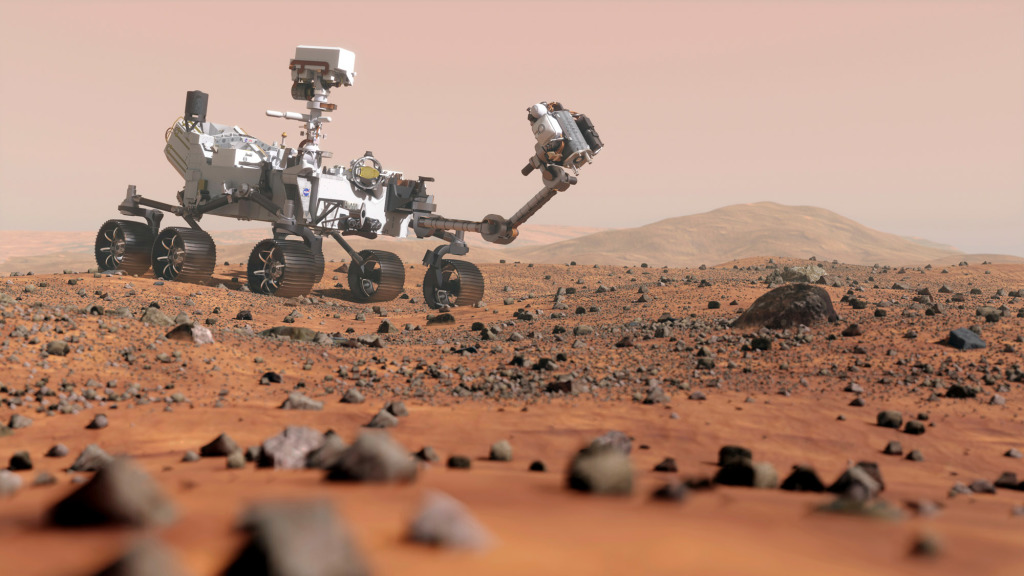

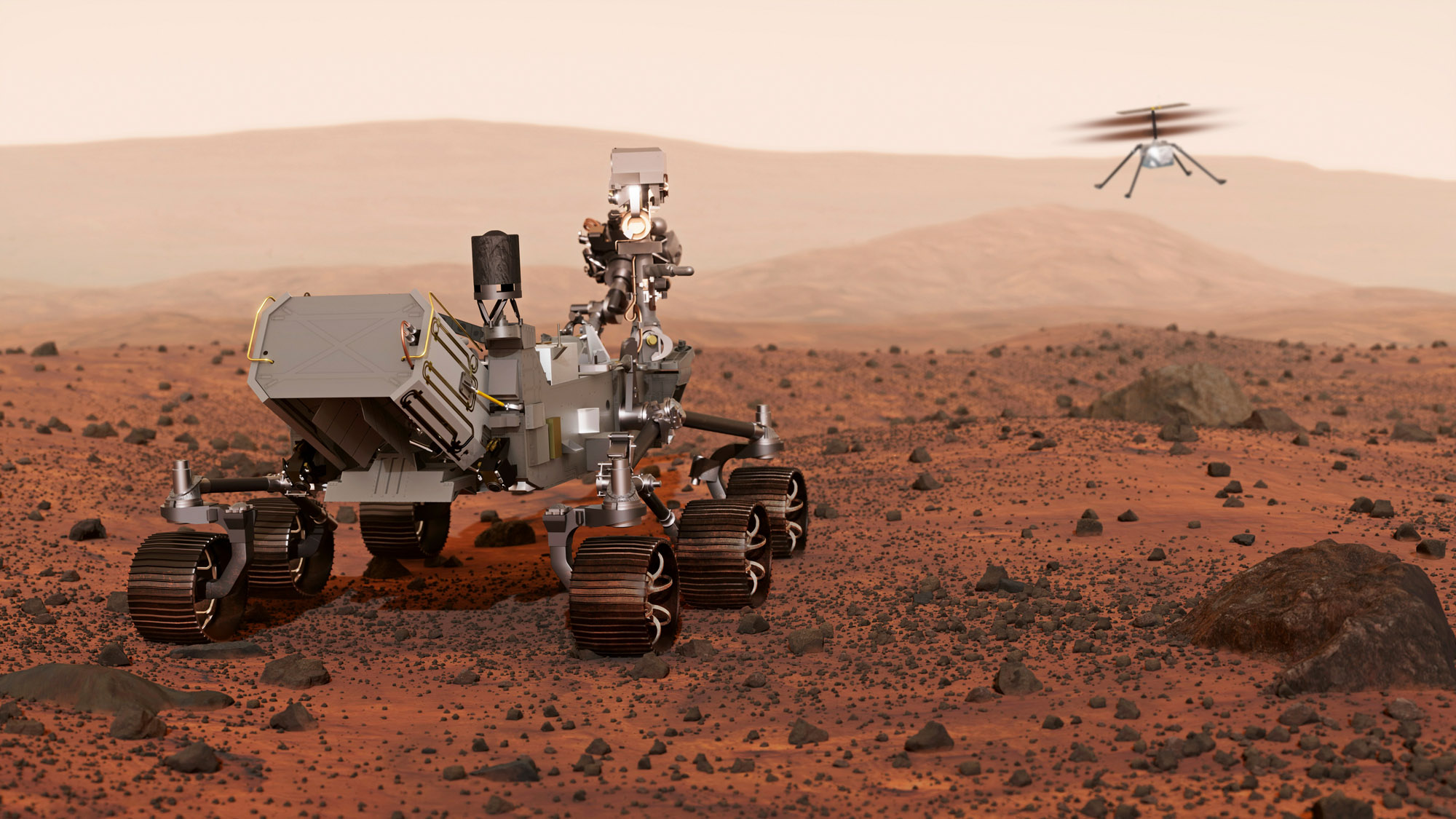

Space missions are always a good source of inspiration. I recently did a whole slew of images and animations based on the Mars Perseverance mission. I also get inspired by others’ work. The BBC documentary The Planets had some great animations in it – which sadly they did not get me to do! – and I did some of my own inspired by these.

Another recent first for me was learning how to create 3D models in Blender. I had done a little modelling before, simple things, but modelling a dinosaur, for example, was beyond me. I had no idea where to even start. That’s changed now and I can model my own animals without buying them on sites like Turbosquid.

How do you see the development of imagining technology influencing the direction of your work?

Well, I was hoping that virtual reality would take off but it seems to have stalled. I learned how to create VR images and the results looked amazing. Instead of a 2D scene or animation, I can create an entire world that you can immerse yourself in. It’s a whole new way to experience art.

What is your best/favourite image in your collection?

I have nearly 3000 images. Picking a favourite is impossible!

But if you really insist, one of my favourite space images is a painting I did (in acrylic) called Wish You Were Here. The original was ok but I prefer my digitally modified version of it (F032/7226).

It shows an alien Earth-like moon with an ocean, a beach, and the moon’s parent planet in the sky. The scene is based on Durdle Door, a natural rock arch on England’s south coast.