Alexander Semenov is an underwater photographer based at Moscow State University’s White Sea Biological Station. A marine biologist, specialising in invertebrate animals, Alex takes his camera below the surface to show us a world we’ve never seen before.

How did it all begin?

During my time in high school, we focused on natural science, which led to my first summer of field practice at the White Sea. It was my first encounter with marine biology, and it was beautiful. I loved it so much that it inspired me to continue working in this field.

From that moment, my point of interest was to study octopus behaviour, so I chose the department of Zoology of Invertebrates in the Lomonosov Moscow State University.

I began working at the White Sea Biological Station (WSBS) in 2017 as an assistant diver. WSBS dive station is located right at the Polar circle, which is great for serving a variety of underwater scientific needs. I became the Head of our diving team and now I’m leading a crew of hard-core scientific divers. We are used to diving in unfavourable conditions, successfully conducting complex research projects.

I started underwater photography shooting small invertebrates just for fun; I used an old DSLR camera without any professional lights or lenses. I ended up with some good shots. My boss was inspired to buy a semi-professional camera set up with underwater housing and strobes.

After years of trial and error, I finally call myself a professional photographer. I’m quite proud of what I’m doing now.

What drew you to invertebrate animals?

'They are just awesome'

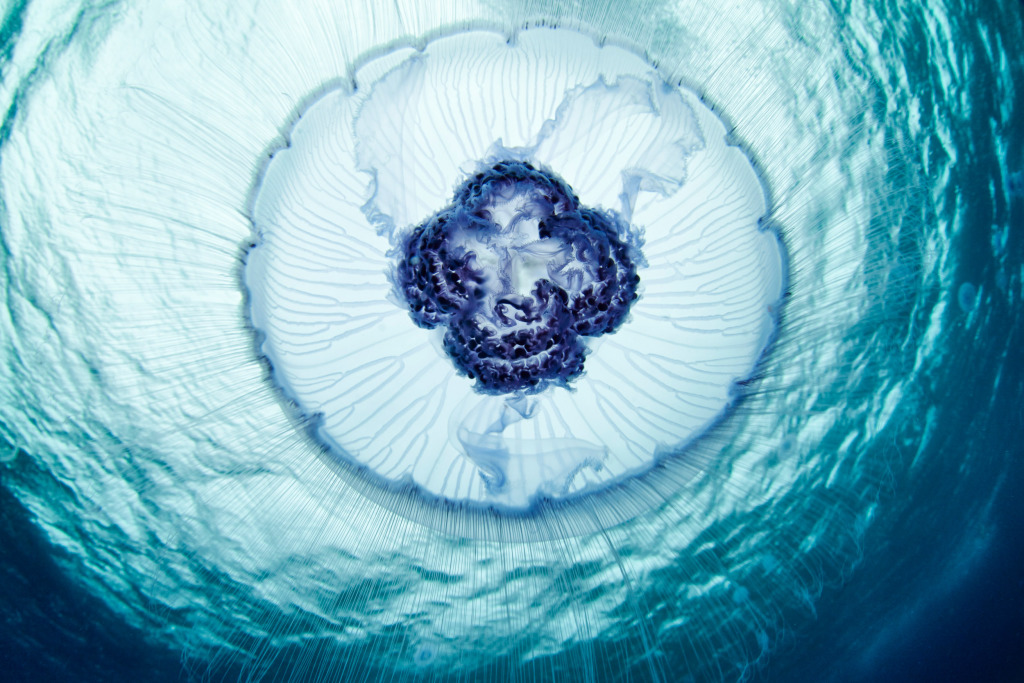

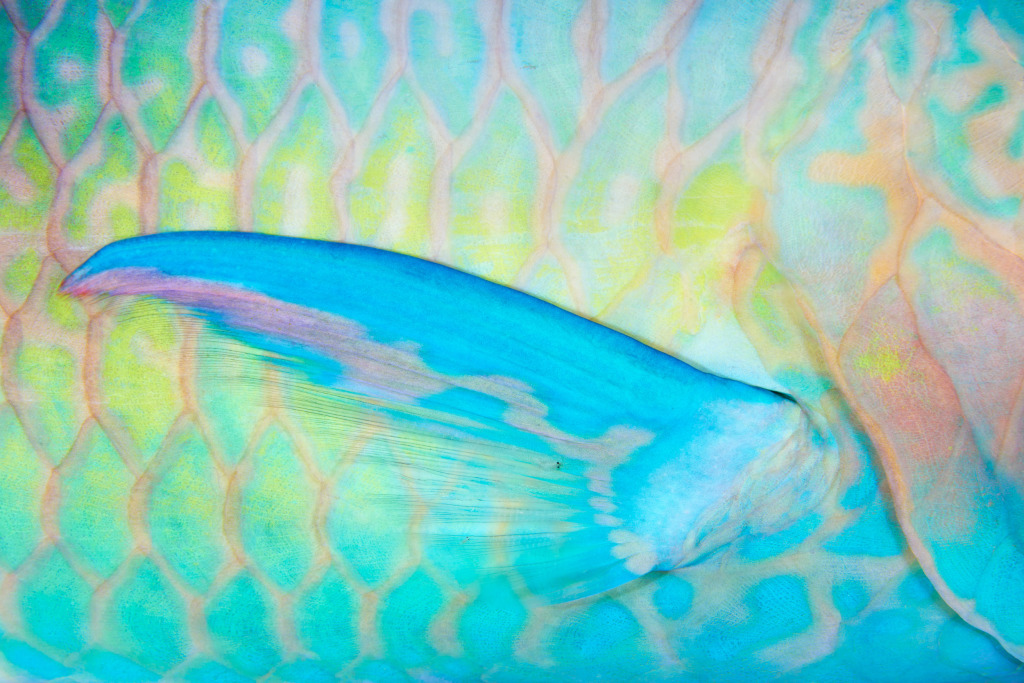

First, they are completely unearthly. Their forms, colours, and way of life are something from another world. Secondly, they make up about 95% of the total animal biodiversity in the oceans. There are hundreds of thousands of absolutely incredible creatures in the world’s oceans that keep surprising even the most experienced marine biologists.

The ocean is a parallel universe, another world inhabited by amazing creatures. Many of these creatures are so gentle and ephemeral that even a single touch can be the last event in their lives.

It’s extremely difficult and sometimes just impossible to study them in the lab. For example, the lion’s mane jellyfish (Cyanea capillata) can grow up to 37.5 meters long with the dome about 2.3 meters in diameter, making it too large to keep in an aquarium.

Diving with cameras, it’s possible to observe and record these creatures’ life and behaviour in their own territory; we can see and study their movement mechanics, feeding habits, growth and reproduction cycles, which life forms they tolerate and which are their enemies. It is very challenging to obtain this priceless information about life in the depths of the ocean, but this is probably one of the most interesting tasks.

When was the first time you realised your work was well-received?

I sent my portfolio to one very well-known magazine and in less than 10 minutes they asked me to invoice for a double page spread. Before that, I had a photo-blog with a few hundred followers, this quickly grew to thousands and they motivated me to grow and move forward.

Do you think you’ve improved awareness of marine biology?

I hope so!

The World Ocean is a living system of unimaginable scale; the oceans take up 71% of the surface of our planet and life is dispersed throughout the whole entire volume, not just the surface. All the exploration of the oceans, including divers, deep water robots, and manned submarines is actually negligible.

During the last 2000 years, we have discovered a little more than 245,000 species of marine organisms, according to scientists’ estimates, that’s only 8-10% of ocean life. It means that somewhere in the depths there are 2-3 million species that have never been seen by human eyes. Ever. We do not even know what they might look like!

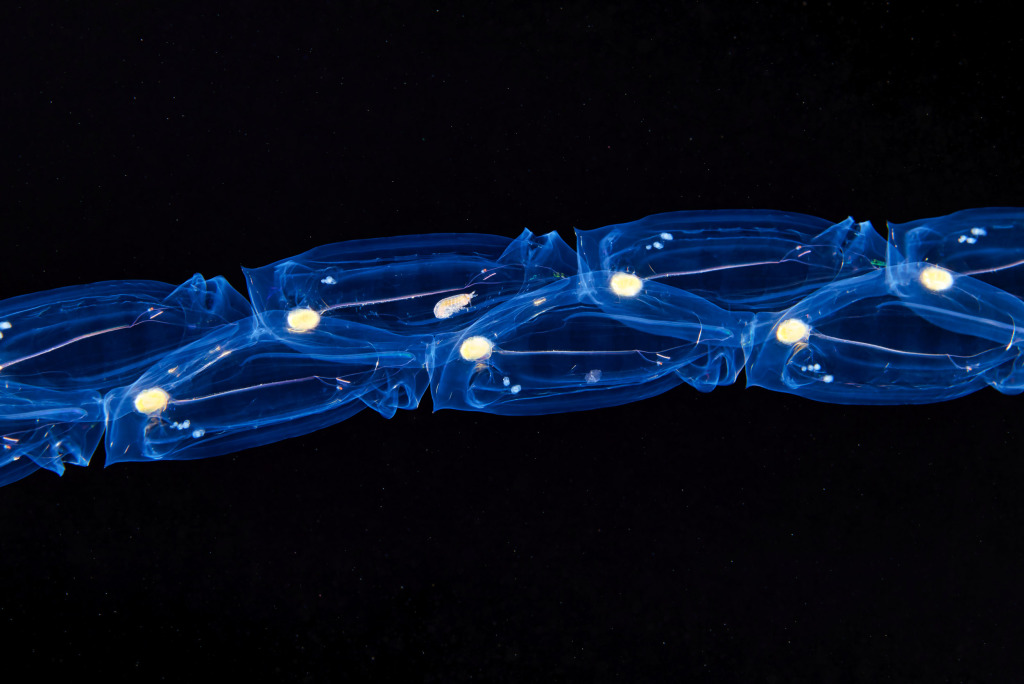

Everyone knows about sharks, whales, octopuses, jellyfish, and some other large marine animals. But the average person has never heard of salps, siphonophores, comb jellies, appendicularians, ascidians, and many others.

I aim to show a world full of strange and wildly interesting things. By publishing vivid science books, conducting classes at schools, creating lectures and movies about the underwater world, we can widen kids’ horizons, teach them new things and inspire everyone to better understand marine biology and science in general.

Who influences your work?

My wife.

She says all the time that this can be done better!

Do you enjoy public lectures and who attends?

Oh yes! This is one of my favourite activities. When I’m not in the field/sea, I have 2 to 5 lectures in a week, mostly in primary schools, for kids from 7 to 12 years old. This is an opportunity to show them giant worms with alien-like retractable throat, sea angels hunting and other cool photos and videos. When they are impressed and sit with their mouths agape, this is the best moment to cram some new knowledge into them.

Where’s the most unique place you've dived?

The most interesting and cool place that I visited was the northern Kuril Islands. This is a ridge of volcanic islands separating the Sea of Okhotsk and the Pacific Ocean. Not only is this a very distant and practically uninhabited area, where only a few hundred people have access per year, it is also a real nature sanctuary. Underwater life there is just fantastic and unexplored. It is likely that I was the first person to dive there with a camera a few years ago.

What do you think your best achievement is so far?

Hmmm… I have never thought about it. Probably the fact that I survived in all my expeditions and the most difficult dives. Or the fact that I continue to work in the same field with even more energy and passion after 12 years.

The best image in your collection?

I’m a biologist, I can’t choose!

I have some really good photos of Clione limacine.

A portrait of Alitta (Nereis) virens became one of the photos of the year 2012 in Nature magazine.

What are you working on at the moment?

I’m now at the White Sea Biological Station with my team diving under the ice and filming sea angels behaviour for the next 1.5 months, a chilling experience. We are also working on a big exhibition project in Russia and two new documentaries.

We’re keeping busy!

What is next for you?

For the last few years, I have my own project named ‘Aquatilis’. It’s an expeditionary educational and scientific project aimed at finding, filming and studying the most extraordinary creatures of the World Ocean.

We have been working on our own and in collaboration with many cool guys and companies. We have big plans but it depends on funding. We’re not a commercial production company and don’t have (financial) sponsors. We are self-funding and don’t receive a salary. Hopefully, it will change one day.

I dream about having my own small biological station somewhere in the Pacific Ocean, probably at the south part of the Sea of Japan. I hope to settle there in 10 years’ time. Big things move slow.